Evacuation, Occupation, And Farewell: The Last Chapter of The Revolutionary War In New York City

by Mary Tsaltas-Ottomanelli

Mary Tsaltas-Ottomanelli takes a close look at the months following the British surrender at Yorktown and explores the final chapter of the Revolutionary War in New York City.

New York City was considered a key to winning the Revolutionary War—whoever controlled the city, controlled the war. In 1776, it stood as a central position within the colonies because of its strategic access to commerce and waterways. The Patriots controlled New York City on July 8, 1776, when the army gathered to hear one of the first readings of the Declaration of Independence. Just a few weeks later, the Continental Army experienced one of its worst defeats at the Battle of Brooklyn, forcing the city's first evacuation by General Washington. It would take seven years for the city's next evacuation – this time by the British.

The Garrison Known As Torytown

Surrender of Lord Cornwallis, John Trumbull. Courtesy of Architect of the Rotunda

As legend held for over a century, the British bands played The World Turned Upside Down as British Cornwallis ordered the white flag of surrender at the Battle of Yorktown on October 19, 1781. As 8,000 British soldiers laid down their arms in the surrender, the band played, "Yet let's be content, and the times lament, you see the world turn'd upside down. The world needed to keep turning." The world remained upside down for another two years until the war ended in the last British enclave of the Revolutionary War – New York City.

When the Treaty of Paris was signed on April 15, 1783, New York City was still occupied as the last British stronghold in the former colonies. Shortly thereafter, Sir Guy Carleton, the Commander-in-Chief of the British forces in North America, received his final orders to begin the evacuation of the city which he believed could take upwards of four months. Carleton spent most of the Revolutionary War in Canada as the Governor of Quebec and was knighted for his commandership during the Siege of Quebec. Shortly after the surrender at Yorktown, Carleton was named General Henry Clinton’s successor.

Colonel Sir Guy Carleton, Courtesy of Library of Congress

Before the outbreak of war, New York City was one of the colonies' major powerhouses, rivaling Philadelphia. The seven-year occupation of the city by the British reduced one of the greatest metropolises to a shell of its former glory. By 1783, the city was nothing more than a garrison for soldiers and a haven for thousands of refugees. At any given point during the British occupation, "the number of troops on and around Manhattan island fluctuated somewhere 3,000 and 20,000" with a large force kept on nearby Staten Island to protect from a surprise attack from New Jersey.[1] Life for British soldiers living in the city proved difficult. Most soldier’s living quarters were repurposed churches or other large structures like King’s College. They were subject to illness due to contaminated foods and lack of access to clean water. Soldiers also worried about "epidemics of smallpox, cholera, and yellow fever that swet the city with grim regularity."[2]

Two significant fires destroyed the city – the first in 1776, which destroyed a third of the city's structure, and the second in 1778, which destroyed the waterfront. Almost immediately, the effect of British occupation was felt on the city. By the end of 1776, "the dearness of food, the inadequate supply of fuel, the eager desire to have news from the front, the return of the sick and wounded…the absence of civil government, the growing importance of privateering, the squalor of the group of shanties and tents known as canvas town amid the blackened ruins left by the fire, the well-to-do families now forced to live on charity.”[3]

The city was placed under martial law, providing little protection for civilian lives and property. The British military's rampant corruption was a common occurrence that made New York City a dangerous city; for years, accounts of theft, fraud, and murder by English soldiers were documented in newspapers. The streets were covered in filth with no sanitation collection, schools were closed, and churches were converted into "hospitals, prisons, barracks, riding schools, or storehouses; the pews…torn out, the window-lights broke.”[4] Nearly every tree in the city was cut down to make firewood, and when there were no trees, they turned to wooden fences.

Once Carleton received the official word the Treaty of Paris was signed, he arranged a full-scale British evacuation of more than 30,000 British and Hessian troops and relocated an estimated 27,000 refugees to other parts of the empire. Carleton loosened the restrictions for traveling in and out of the city as well. By September, the newspapers advertised ships bound for other parts of the British Empire. It seemed as if the whole city was once again moving, and "the streets were filled with men, women, and children heading for the wharves.”[5] The majority of the population could not afford the passage to Great Britain for their families and belongings; more loyalists chose to settle in Nova Scotia than any other part of the empire during the evacuation.

Samuel Fraunces

Samuel Fraunces was a known Patriot in the years leading to the outbreak of the war. He opened the tavern to patriot groups, like the Sons of Liberty, who used the tavern as one of their headquarters, where they possibly plotted the New York Tea Party on April 22, 1774. By the British occupation on September 15, 1776, Fraunces had left for Elizabethtown, New Jersey, leaving his son-in-law, loyalist Charles Campbell, responsible for the Queen's Head. During the war, the tavern was irregularly opened for food and drink due to the scarcity of foods and other goods.

In June 1778, Fraunces was captured as a prisoner of war and brought to work as the family cook for General James Robertson, the acting Governor of New York. Recognizing the opportunity, Fraunces acted as a spy, listening to conversations during dinner parties hosted by Robertson. He also used his position as a chef to sneak table scraps to American prisoners, gave them clothing and money when possible, and even assisted some with escape.

General Washington’s Farewell Orders

Disbanding the Continental Army, at New Windsor, New York, November 3, 1783 / drawn by H.A. Ogden. Courtesy of Library of Congress.

After the Treaty of Paris formally ended the war, most of the Continental Army was disbanded in late 1783. Washington was unwilling to step down as the commander in chief of the Continental Army until the final peace treaty was signed and all British had evacuated New York. For much of the two years following the surrender at Yorktown, Washington struggled to maintain the Continental Army, fearing the British would catch wind of the estrangement and refuse to keep the peace. Just months earlier, in March 1783, Washington had suppressed an attempted military coup, known as the Newburgh Conspiracy. Continental soldiers, angry about not having been paid, threatened to take action against the Congress. Once notified of the attempted coup, Washington addressed his officers in an emotional plea which reinforced the sacrifices each soldier, including himself, had made for the fight for independence. While reading the address, Washington reached for his glasses and gestured, "I have not only grown gray, but almost blind in service to my country.”[8]

As the Continental Army’s reoccupation of New York City crept closer, Washington directed Major General Knox to deliver his Farewell Orders to the Continental Army in Rocky Hill, New Jersey, on November 2, 1783. Washington addressed the Continental Army as “one patriotic band of Brothers,” and acknowledged that the Continental Army was the first volunteer army of citizens who fought together for freedom. He reminded them that they had accomplished the impossible, “the singular interpositions of Providence in our feeble condition were such, as could scarcely escape the attention of the most unobserving, while the unparalleled perseverence of the Armies of the United States, through almost every possible suffering and discouragement, for the space of eight long years, was little short of a standing Miracle.”[9]

The remaining standing army was condensed into the 1st and 2nd Regiments of the Legion of the United States under the command of Major General Anthony Wayne. By the end of November, the remaining army joined the General for the last symbolic act of taking New York City back from the British.

Evacuation Day

After the final version of the Treaty of Paris signed on September 3, 1783, Carleton ordered the final British withdrawal out of Long Island and upper Manhattan by November 21. As the remaining 6,000 British troops left, American forces began occupying the abandoned garrisons. General Washington, joined by New York Governor George Clinton, rode into Harlem by McGowan's Pass Redoubt, now on Central Park's northwest corner. It would take three days for the evacuation to reach the end of the island.

1783 Evacuation Day Route, from “Evacuation Day” by James Riker

On the cold and clear morning of November 25, 1783, General Henry Knox began marching into New York City with around 800 American soldiers, consisting of "a troop of dragoons in front, an advance guard of light infantry, a few artillery batteries, and several infantry regiments.”[10] The American detachment waited right outside the city's northern boundary waiting for the cannon fire which would that the last of the British were leaving. Cheering crowds gathered along the Bowery and down to Cape’s Tavern, where they waited for the American flag to be raised over Fort George.

The British left one last parting gift for the Americans during their evacuation – a Union Jack flag still waving in the wind at Fort George. The British nailed the flag to the pole, the halyard removed, and the pole greased. Until the United States flag was raised, the Americans could not officially take back to New York City.

John Van Arsdale, a young sailor, volunteered to take on the impossible task: removing the last vestige of British occupation. Arsdale fashioned a pair of wooden cleats and attempted to climb the greased pole, but it proved unstable. He returned from a local hardware store with a saw, hatchet, gimlets, and nails. It was reported that "willing hands sawed pieces of the board, split and bored cleats, and began to nail them on.”[11]

Evacuation of New York by the British, November 25, 1783, Courtesy of Library of Congress

The group fashioned a ladder to help Arsdale ascend the pole, replacing the Union Jack with the Stars and Stripes. While the American flag billowed into the air, the cannon salute began. Artillerymen began firing the thirteen-gun salute, signaling to Washington to start the final leg of the procession into Fort George and officially take possession of New York City.

Colonel Benjamin Tallmadge, who participated in the Evacuation Day march, notes in his memoir:

“Gen. Knox, at the head of a select corps of American troops, entered the city as the rear of a select corps of American troops, entered the city as the rear of the British troops embarked; soon after which the Commander-in-Chief, accompanied by Gov. Clinton and their respective suites, made their public entry into the city on horseback, followed by the Lieut.-Governor and members of the Council.”

Washington rode next to Clinton as a sign of respect and "to show his deference to civilian authority and was also accomplished by the West Chester Light Dragoons, a surefire local crowd-pleaser.”[12] They were also joined by General Alexander McDougall and Colonel John Lamb, both prominent members of the Sons of Liberty. They marched down Queen Street (now known as Pearl Street) and Broadway, stopping at Cape's Tavern for a brief reception. Returning for the first time since 1776, Washington saw a vastly different image of New York City. Looking past the crowds of celebrations, he "could discern a desolate city of empty lots, burned-out buildings, and churches despoiled of pews to house British troops.”[13] Trinity Church, which burned down in the Great Fire of 1776, still lay in ruin and would not be rebuilt until after the occupation.

At Cape’s Tavern, a citizen’s address to Washington was read aloud:

“Permit us to welcome you to this city, long torn from us by the hard hand of oppression, but now by your wisdom and energy under the guidance of Providence, once more the seat of peace and freedom.”

Washington thanked the crowd for their affectionate address, responding:

“The fortitude and perseverance which you and your suffering brethren have exhibited in the course of the war, have not only endeared you to your countrymen, but will be remembered with admiration and applause to the latest prosperity.”[14]

Thirteen Toasts

That evening, Governor Clinton hosted a dinner at Fraunces Tavern in honor of General Washington with over a hundred guests in attendance. A series of thirteen toasts “were drank expressive of the esteem in which the United States of America, held the exalted Personages with whom they have formed such respectable alliance, and equally calculated to inspire a general veneration for public freedom.”[15] The thirteen toasts were as follows:

The United States of America

His Most Christian Majesty

The United Netherlands

The King of Sweden

The American Army

The Fleet and Armies of France, which have served in American

The memory of those Heroes who have fallen for our freedom

May our county be grateful to her Military children

May justice support what courage has gained

The Vindicators of the rights of mankind in every quarter of the globe

May America be an asylum to the persecuted of the earth

May a close union of the States guard the Temple they have erected to liberty

May the remembrance of this Day be a lesson to Princes

Although there was much unknown about the new nation's future, the next few days were dedicated to celebration. That evening there was "a grand display of rockets, and the blaze of bonfire at every corner, made a fitting sequel to the events of the day.”[16]

Afterward, Governor Clinton received a receipt for the dinner, which shows just how much entertainment was had that evening:

Entertainments

November 25th 1783

His Excellency Governor Clinton To Saml. Fraunces Dr.

To an Entertainment…………………………………………………………………………………. £30. .4. .0

To 75 Bottles of Madeira at 8/ …………………………………………………………………… 30

To 18 Ditto of Claret at 10/ …………………………………………………………………………9. .

To 16 Ditto of Port at 6/ ……………………………………………………………………………..4. . 16..

To 24 Ditto of Porter at 3 / …………………………………………………………………………3. . 12..

To 24 Ditto of Spruce at 1/ …………………………………………………………………………i. .4. .

To Lights 60/ Tea & Coffee 64/ ………………………………………………………………6. .4. .

To Brokeg ……………………………………………………………………………………………….2. . 2. .

To Punch ………………………………………………………………………………………………..10.. 10..

£97..12..

The above Bill is for an Entertainment on taking Possession of the City when the British evacuated the Southern District. Rec^ the Contents in full 2d Feby. 1784.[17]

The Next Ten Days

The morning after, Alexander Hamilton joined Washington to pay a visit to 23 Queen Street, the residence of Hercules Mulligan. As noted in the Recollections and private memoirs of Washington, "he breakfasted with M-----, to the wonder of the Tories and the perfect horror of the Whigs.”[18] As a secret member of the Sons of Liberty, Mulligan remained in the city during the Revolutionary War, keeping his shop open to wealthy British businessmen and high-ranking British military officials – collecting their measurements and secrets. It is worth noting that Mulligan's intelligence successfully thwarted two attempted assassination attempts on the General. Washington's breakfast was a public indication of Mulligan's true patriot allegiance.

For Washington, the next few days were filled with more celebratory dinners and receptions throughout the city. Washington attended several receptions hosted by Governor Clinton, including one on December 1, in honor of the French ambassador, the Chevalier de la Luzerne. Many of the banquets were exclusively attended by military and social elites in the city, while public celebration and ruckus took form in raising liberty poles and more cannon-fire.

Captain William Price organized a massive display of fireworks on the evening of December 2. The Independent New York Gazette reported that the spectators were speechless "unless when they some times manifested their satisfaction by loud huzzas.” [19] A graduation of three sets, including rockets, stars, moons, and suns, captivated the onlookers from the beginning to the end. To read more about the General’s activity in New York City see “Itinerary of General Washington, from June 15, 1775 to December 23, 1783”

George Washington’s Bill of Receipt from Samuel Fraunces, November 1783, Courtesy of Library of Congress

Washington's relationship with Samuel Fraunces began on April 13, 1776, when he attended a court-martial at the tavern. This is likely the first time the two men met. With his headquarters at No. 1 Broadway, the General likely called upon Fraunces' takeout service, ordering some of the best food and drink selection in the city. Washington hired Fraunces to cater the peace negotiation meetings with Carleton earlier in 1783. Fraunces' friendship with Washington made an impression when Washington hired him to be the first presidential steward in 1789. Fraunces was responsible for overseeing the operation of the house and a staff of twelve. Fraunces also selected food for Washington's table and supervised its preparation. Fraunces rejoined the Washington's household in 1790 when the federal government moved to Philadelphia and remained until 1794.

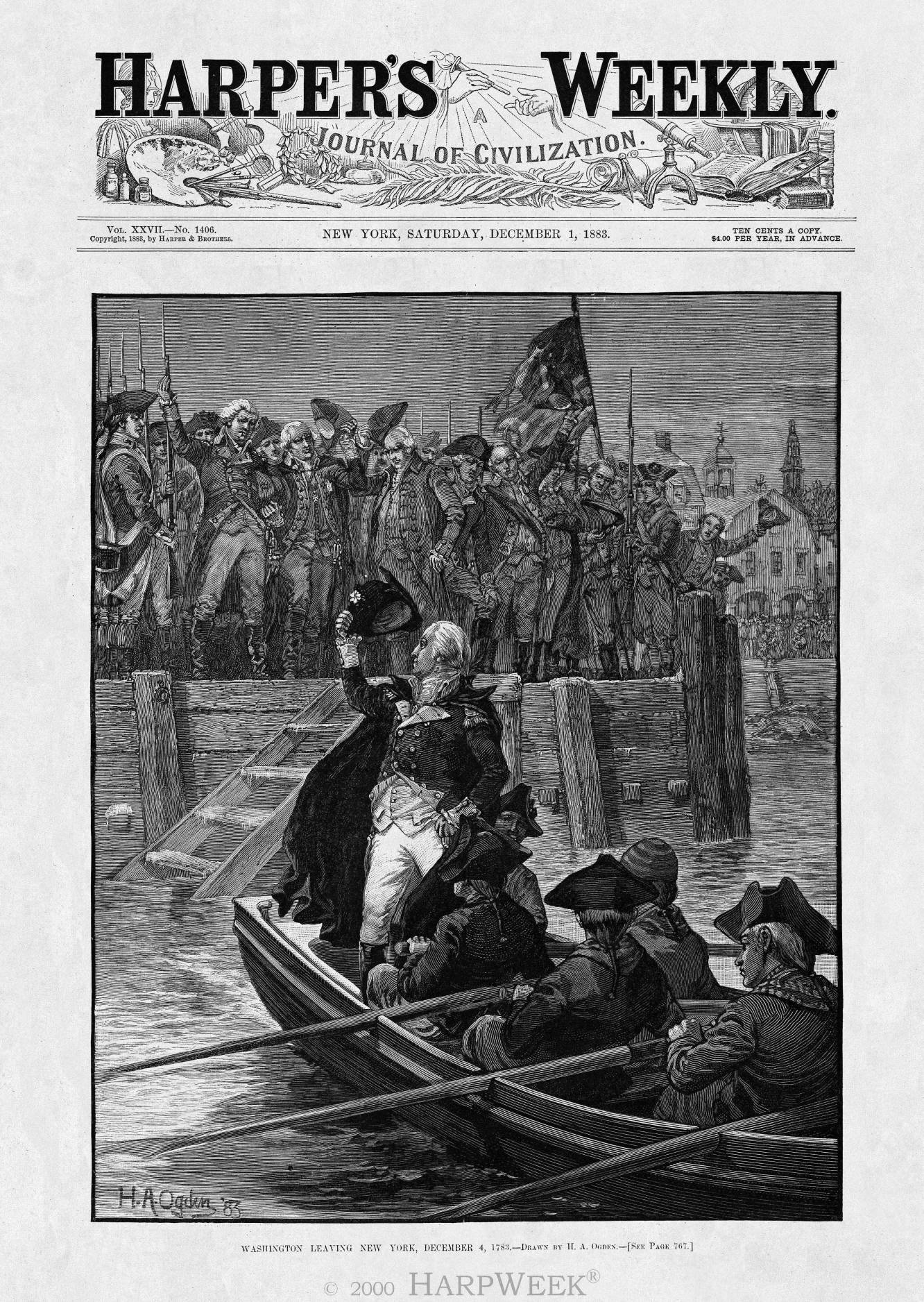

Washington’s Farewell

On December 4th, Washington received word from Carleton that the last of the British troops sailed from Long Island and Staten Island. Washington invited his officers to join him at Fraunces Tavern for one last celebration, and to bid them farewell.

Shortly before noon, Washington assembled about thirty soldiers to the Long Room at Fraunces Tavern for his last goodbye. There is only one known complete account of this event, written by Colonel Benjamin Tallmadge. From his 1830 memoir, he recounts:

“We had been assembled but a few moments when his excellency entered the room. After partaking of a slight refreshment in an almost breathless silence the General filled his glass with wine and turning to the officers said, “With a heart full of love and gratitude I now take leave of you. I most devoutly wish that your latter days may be as prosperous and happy as your former ones have been glorious and honorable.”[20]

After the officers had taken a glass of wine General Washington said, “I cannot come to each of you but shall feel obliged if each of you will come and take me by the hand.” General Knox, the closest officer to Washington, walked up to the General and the two hugged and kissed with tears running down their faces. Tallmadge recalls, “In the same affectionate manner every officer in the room marched up and parted with the general in chief. Such a scene of sorrow and weeping I had never before witnessed and fondly hope I may never be called to witness again.”

The farewell was a solemn event not just for General Washington, but for each of the officers in the room. With the last of the British gone from American soil, the Revolutionary War was truly over, and it was time to begin anew. The Farewell "comprised the courageous soldier, the invaluable patriot, and the sincere friend to the interest of society.”[21] After nearly eight years of hardship, it was done. This was the last time many of these men would see each other again. The native New Yorkers remained in the city, ready to rebuild it into the economic powerhouse before the war. Foreign officers, including Thaddeus Kosciuszko, took the ideals of the Revolutionary War back home with them; Kosciuszko would spend the next decade fighting for Poland's independence.

Author’s note: Members of Sons of the Revolution in the State of New York, Inc. (who own and operate Fraunces Tavern Museum) and Fraunces Tavern Museum staff have conducted research attempting to conclude which officers were in the Long Room during Washington’s Farewell. We can conclude, at minimum, General Knox, Colonel Tallmadge, McDougall, and Kosciuszko were in attendance. In addition, it is likely Washington’s aides-de-camp were also in attendance with important New York City officials, like incoming Mayor James Duane.

Not long after, the officers escorted the General to the Whitehall wharf, where he boarded a barge that took him to Paulus Hook (now Jersey City). Washington raised his tricorne hat at the crowd as he departed as they cheered his departure. Washington’s next stop was the State House in Annapolis, where the Continental Congress was meeting, resigning his commission as Commander-in-Chief.

After stopping in Philadelphia, Washington reached Annapolis on December 19. In the days leading up to his resignation, he met with General Horatio Gates, William Smallwood, and members of congress to discuss the details of his departure.

On December 23, Washington addressed congress for the last time as General of the Continental Army. He delivered his emotional speech to the congress, remarking that "having now finished the work assigned me, I retire from the great theatre of action, and bidding an affectionate farewell to this august body, under whose orders I have so long acted, I here offer my commission, and take my leave of all the employments of public life.”[22]

General George Washington Resigning His Commission, John Trumbull, Courtesy of Architect of the Capitol

Washington's willingness to relinquish military powers is hailed as one of the most symbolic moments of the Revolutionary War. Washington intended his resignation to "emphasize the power of Congress, as is evident with the final stipulation that 'when the General [Washington] rises to make his address, and also when he retires, he is to bow to Congress, which they are to return by uncovering without bowing.’”[23] It was time for Washington, now a private citizen, to return home to Mount Vernon and Martha, as he promised his return by Christmas.

The Legacy Of Evacuation Day

Public celebrations for Evacuation Day were primarily a locally celebrated holiday by New Yorkers. In the years after, for their 1787 full-dress review, the garrisoned troops in New York City marched up Broadway to the Commons (now City Hall Park), cheered on by thousands of onlookers. They participated in a formal celebratory rifle salute known as a feu de joie ("firing of joy"), which was reserved for military victories. In this salute, each soldier fires from right to left, then each soldier fires all at once, creating a cacophony of different sounds. Before Evacuation Day celebrations, the feu de joie was used in celebrations for the signing of the Declaration of Independence. The celebrations continued like this for much of the 1790s. By the 1830s, fewer and fewer New Yorkers who lived through occupation were still alive and didn’t have a direct connection to Evacuation Day. There was a shift from the "anniversary of the evacuation of the British troops" to simply Evacuation Day, which "symbolized the change in the meaning of the day, from an event experienced by the Revolutionary generation to an event memorialized by their children and grandchildren.”[24]

Centennial Celebrations

Bicentennial Evacuation Day Parade Poster, Part of the SRNY archive

Evacuation Day celebrations were revived in New York City for its 100th anniversary in 1883. Spearheaded by John Austin Stevens, a founder of the Sons of the Revolution in the State of New York, Inc., spearheaded the preparations for the centennial celebrations. The 1883 Evacuation Day parade would be the largest in the holiday's history due to the attention it received nationally, with over one million attendees, 25,000 marching troops, a marine pageant of 300 warships, and the attendance of President Chester A. Arthur and Governor Grover Cleveland.

Unveiling of John Quincy Adams Ward's statue of George Washington on Evacuation Day, Courtesy of Manhattan Historical Site Archive

A new statue of George Washington was unveiled during the Centennial Celebrations. The Chamber of Commerce commissioned John Quincy Adams Ward to design the statue, which was to be placed at approximately the same location and height that Washington stood while sworn in as President of the United States in 1789. The statue, located today on the steps of Federal Hall, stands at 12 feet 6 inches and weighs nearly 6,000 pounds.

Evacuation Day celebrations during the 20th century dwindled for several reasons. As New York City’s diverse population grew, less individuals had a connection to or knowledge of this colonial-era holiday. The outbreak of World War I and the United States’ alliance with Great Britain also halted celebrations, as a sign of respect, until 1919. That year’s observance included “sixty veterans of the Old Guard, the 3rd U.S. Infantry, raised the flag a final time” with a crowd of 45,000 spectators.[25] Ultimately, Evacuation Day celebrations were overshadowed by the national observance of Thanksgiving.

Celebrations Since and Today

During the 1983 bicentennial observance, SRNY and Fraunces Tavern Museum debuted a museum exhibition on Evacuation Day's history and its connection to 54 Pearl Street. In 2017, the area around Bowling Green was renamed “Evacuation Day Plaza,” thanks to the efforts of SRNY member and former president, Ambrose M. Richardson III. The Lower Manhattan Historical Association continues to commemorate Evacuation Day with a parade from Fraunces Tavern to the Plaza where they pull down the British flag and raise the American flag just as John Van Arsdale did in 1783. SRNY continues holding their annual Evacuation Day Dinner, where the thirteen toasts are given as they were in 1783.

Fraunces Tavern Museum also hosts a Washington’s Farewell reenactment in the Long Room. On the Sunday closest to December 4th, the museum allows visitors to witness the farewell as if they were present in 1783.

Bibliography

Chernow, R. (2011). Washington - A Life. Penguin Books.

Custis, G. Washington Parke. (1859). Recollections and private memoirs of Washington. Washington, D.C.: Printed by W.H. Moore.

Hood, C. (2004). An Unusable Past: Urban Elites, New York City's Evacuation Day, and the Transformations of Memory Culture. Journal of Social History, 37(4), 883-913. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/3790071

Knight, E. C. (1901). New York in the Revolution as Colony and State Supplement. Albany, NY: New York State Library.

Polf, W. A., New York State American Revolution Bicentennial Commission. (1976). Garrison town: the British occupation of New York City, 1776-1783. Albany: New York State American Revolution Bicentennial Commission.

Redding, N. A. (2020, July 11). George Washington Resigns his Commission in Annapolis. Retrieved from https://www.preservationmaryland.org/george-washington-resigns-his-commission-in-annapolis/

Riker, J. (1883). "Evacuation day", 1783: its many stirring events: with recollections of Capt. John Van Arsdale, of the Veteran corps of artillery, by whose efforts on that day the enemy were circumvented, and the American flag successfully raised on the battery. New York: Printed for the author.

Smith, W. (Publisher)., Smith, W., Durst, S. B., P.S. Duval & Son. (1860). Washington's triumphal entry into New York.: This beautiful print ... was executed and printed in oil colors, at the establishment of P.S. Duval & Son, Philadelphia, and is the largest specimen of chromolithograph ever executed. ... [Philadelphia: Published by William Smith.

Tallmadge, B., Johnston, H. Phelps. (1904). Memoir of Colonel Benjamin Tallmadge. New York: Gilliss Press.

Wertenbaker, T. Jefferson. (1948). Father Knickerbocker rebels: New York City during the Revolution. New York: C. Scribner's Sons.

Footnotes

[1] Polf, 30

[2] Polf, 34

[3] Wertenbaker, 124

[4] Riker, 8

[5] Wertenbaker, 261

[8] The Newburgh Conspiracy, from https://www.mountvernon.org/george-washington/the-revolutionary-war/the-newburgh-conspiracy/

[9] “Washington’s Farewell Address to the Army, 2 November 1783,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-12012.

[10] Hood, 885

[11] Riker, 16

[12] Chernow, 450

[13] Chernow, 450

[14] Smith, Washington's triumphal entry into New York.

[15] December 1, 1783, Independent Journal

[16] Riker, 19

[17] Knight, 167

[18] Custis, 51

[19] December 6 1783, Independent New York Gazette

[20] Tallmadge, 96

[21] Independent Journal Dec 8 1783

[22] Redding

[23] https:// Resignation of Military Commission. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.mountvernon.org/library/digitalhistory/digital-encyclopedia/article/resignation-of-military-commission/

[24] Steeshorne, J.E. (Fall 2010). Evacuation Day. New York Archives, Volume 10, Number 2. 10-13

[25] Ibid