Built by the De Lancey family in 1719, 54 Pearl Street has been a private residence, hotel, and one of the most important taverns of the Revolutionary War. View a photo archive that will take you back in time to explore Fraunces Tavern’s illustrious history as the oldest standing structure in Manhattan.

1524-1690

The island of Manhattan was originally inhabited by the Lenape people. This matrilineal tribe-like society occupied the lower Hudson River Valley and the Delaware Valley. The Lenape were skilled hunters but maintained an agricultural society, planting mostly beans, squash, and corn.

The first contact with Europeans was in 1524 when Florentine explorer Giovanni da Verrazzano (1485-1528), in the service of the King Francis I of France, explored North America. The canoeing Lenape encountered Verrazzano’s ship, La Dauphine, in Lower New York Bay. While investigating the Bay, Verrazzano documented what he believed to be a lake, which was actually the entrance to the Hudson River.

In 1609, English explorer Henry Hudson (1560s/70s), was sailing for the Dutch East India Company, looking for easterly passage to Asia and spent ten days ascending the River that now bears his name. His voyage was used to establish Dutch claims to the region. In 1625, New Amsterdam on Manhattan Island became the capital of New Netherland. The trading Hudson did with the Lenape people would be the start of the prosperous fur trade that existed well into the 1800s.

1674-1762

In 1674, after ten years of war and ownership battles between the Dutch and British, the Treaty of Westminster was signed, giving the official ownership of Manhattan to the British.

The land on which Fraunces Tavern stands was occupied by water until the end of the 1600s. By the last decade of the 17th century, New York City was rapidly growing into a leading colonial port. With its naturally protected harbor and its open, multi-ethnic population devoted to commerce, such growth was unstoppable. In order to raise funds for a new market house and ferry building, the city sold lots created by landfill in part of the Great Dock along Pearl Street in 1691. The new block also protected the city hall on the north side of the street from high tide flooding.

The plot of land that is 54 Pearl Street* (landfilled water lot) was purchased from the city by Stephanus Van Cortlandt (1643-1700/01) in 1686. Van Cortlandt was the son of the wealthy and well positioned Olaff Stevenson Van Cortlandt, who immigrated to New Amsterdam (Dutch New York) in 1638.

Stephanus Van Cortlandt’s daughter, Ann, married a young upcoming French Huguenot merchant, Stephen (Etienne) De Lancey in 1700. That same year De Lancey purchased the 54 Pearl Street lot from his father-in-law.

In 1719, De Lancey applied to the Common Council for three and a half more feet to be added to his plot of land on the northwest corner where he planned to build “a large brick house.” It is believed that sometime between 1719 and 1722 De Lancey built a house on the property. The house was probably three stories and constructed with brick, tile, and a lead roof. It is unclear if the De Lanceys ever lived in it, or used it as a rental property.

From 1737 until 1740, Henry Holt rented 54 Pearl Street where he taught dance and held balls. Holt advertised himself as having learned from “one of the most celebrated masters in England” and “dances a considerable Time at the Theatre Royal in Drury Lane.” For New Yorkers striving to keep up with European styles, dance masters like Holt were welcome additions to society.

From 1740 to 1759, the building was most likely used for mercantile and/or residential use, as was fitting for the neighborhood at the time. In 1759, the firm De Lancey, Robinson, & Co. purchased the building. The firm, composed of Stephen De Lancey’s son Oliver, Beverley Robinson, and James Parker, dealt in imported European, West Indian, and East Indian goods, such as rum, sugar, and textiles. Despite its prime location, business was slow. In 1761, the Company offered rooms for rent but were forced to sell in 1762.

Samuel Fraunces purchased 54 Pearl Street in 1762.

1762-1776

Little is known about the famed tavern owner, Samuel Fraunces before the year 1755. It is estimated that he was born around 1722. He is first documented in New York City in 1755 when he registered with the City as a “freeman” and “innholder.” This admission was required by law of all merchants, shopkeepers, and tradespeople who had not been born in the City or served a regular seven-year apprenticeship to a trade.

In 1762, Fraunces opened a tavern under the sign of Queen Charlotte (Queen’s Head Tavern), named for England’s Queen Charlotte, at 54 Pearl Street. In 1765, Fraunces leased management of the Tavern. He resumed proprietorship of the Tavern in 1770.

Taverns were centers of community in the 18th century. Fraunces Tavern was a place where travelers and locals would exchange the latest news and ideas. Entertainment, such as musicians, could be found at the Tavern. The New York Chamber of Commerce was founded at the Tavern in 1768. Many New York clubs and organizations held meetings at the Tavern such as the New York City Sons of Liberty, New York Society Library, the Social Club, the Friendly Brothers of St. Patrick, the Knights of the Order of Corsica, and the Saint Andrew’s Society.

In May 1775, Fraunces opened his doors to the New York Provincial Congress, which was founded in the Long Room. The Provincial Congress acted as a temporary government for the colony throughout the Revolution. They were initially formed as a convention to choose delegates to participate in the Second Continental Congress. Many other revolutionaries subsequently passed through the Tavern.

On August 23, 1775, John Lamb and his artillery company attempted to steal a dozen cannons from the Battery and exchanged fire with the HMS Asia. The battleship bombarded the city from midnight until 3 o’clock in the morning. One of the 18-pound cannon balls from the HMS Asia crashed through the roof of Fraunces Tavern.

The Provincial Congress hosted a banquet in the Long Room on June 18, 1776, for General Washington, his staff, and officers to express their gratitude for the defense of the colony. The party raised 31 toasts throughout the evening, starting with the Congress and the American Army, and ending with “Civil and religious liberty to all mankind.” It was a raucous affair, with officers singing campaign songs accompanied by fife and drum. The final bill presented by Samuel Fraunces, totaling £91, included 78 bottles of Madeira, 30 bottles of port, and sixteen shillings for “wine glasses broken.”

1776-1784

As the rebellion against England started to heat up, Samuel Fraunces left New York for Elizabeth, New Jersey (1775). He left the operation of the Tavern to his Loyalist son-in-law, Charles Campbell, during the British occupation of New York. The Tavern irregularly provided food, drink, and community throughout the war. In 1780, Governor Tyron hosted a dinner for seventy guests at the Tavern, which was attended by the Council and some British generals.

The surrender of the British at Yorktown in October of 1781 did not end the Tavern’s role in the Revolution. Thousands of Loyalist refugees flooded New York City searching for a way to start a new life elsewhere in the British Empire. This included thousands of enslaved people, many of whom left Patriot slaveholders and joined the British Army in return for their freedom. As the Revolutionary War drew to a close in 1783, a joint British and American commission–formed as part of the process to implement the peace–met at Fraunces Tavern to review and deliberate upon the eligibility of some Black Loyalists to evacuate with the British Army. Testimonies were provided by interested persons alongside documentary evidence for the commission to render a decision. These proceedings are now referred to as the “Birch Trials,” named after British Brigadier General Samuel Birch, Commander of the 17th Regiment of Light Dragoons and Commandant of New York, appointed to oversee them.

The Birch Trials were part of a process whereby 3,000 Black Loyalists evacuated New York City between April and November 1783–many of whom had previously been enslaved–the culminating event in one of the largest emancipations of Black people prior to the American Civil War. The names of Black Loyalists who qualified for evacuation were recorded in the Book of Negroes, the compilation of which was overseen by the commission.

By 1783, Fraunces Tavern resumed normal operations and it was reported that “Continental Gentlemen” once again assembled there. The American Commissioners made the house their headquarters while negotiations with the British concerning their evacuation from the City were underway. After several individuals were apprehended with counterfeit money, a trial was held between July and August of 1783 at the Tavern, conducted by the commissioners. The Americans gave a dinner for their British counterparts at the Tavern.

On November 25, 1783, British troops left New York City – the last American city to be occupied. This day would later be referred to as Evacuation Day. George Washington led his Continental Army in a parade from Bull’s Head Tavern in the Bowery to Cape’s Tavern on Broadway and Wall Street. New York Governor George Clinton’s Evacuation Day celebration was held at Fraunces Tavern. During the week of Evacuation Day, George Washington was in the City, and he made use of the Tavern by dining in and ordering take-out.

On December 4, 1783, nine days after the last British soldiers left American soil, George Washington invited the officers of the Continental Army to join him in the Long Room of Fraunces Tavern to bid them farewell. The best known account of this emotional parting comes from the Memoirs of Colonel Benjamin Tallmadge, written in 1830 and now in the collection of Fraunces Tavern Museum. As Tallmadge recalled,

“The time now drew near when General Washington intended to leave this part of the country for his beloved retreat at Mt. Vernon. On Tuesday the 4th of December it was made known to the officers then in New York that General Washington intended to commence his journey on that day.

At 12 o’clock the officers repaired to Fraunces Tavern in Pearl Street where General Washington had appointed to meet them and to take his final leave of them. We had been assembled but a few moments when his excellency entered the room. His emotions were too strong to be concealed which seemed to be reciprocated by every officer present. After partaking of a slight refreshment in almost breathless silence the General filled his glass with wine and turning to the officers said, ‘With a heart full of love and gratitude I now take leave of you. I most devoutly wish that your latter days may be as prosperous and happy as your former ones have been glorious and honorable.’

After the officers had taken a glass of wine General Washington said ‘I cannot come to each of you but shall feel obliged if each of you will come and take me by the hand.’ General Knox being nearest to him turned to the Commander-in-chief who, suffused in tears, was incapable of utterance but grasped his hand when they embraced each other in silence. In the same affectionate manner every officer in the room marched up and parted with his general in chief. Such a scene of sorrow and weeping I had never before witnessed and fondly hope I may never be called to witness again.”

The officers escorted Washington from the Tavern to the Whitehall wharf, where he boarded a barge that took him to Paulus Hook, (now Jersey City) New Jersey. Washington continued to Annapolis, where the Continental Congress was meeting, and resigned his commission.

1785-1795

Fraunces continued running the Tavern as post-revolution life settled down. In early 1785, Fraunces agreed to lease the Tavern to the Confederation Congress for use as office space for the Department of Foreign Affairs and Department of War. Two weeks after the lease was signed, Fraunces, now a resident of New Jersey, sold the Tavern to Brooklyn butcher, George Powers. Shortly thereafter, Congress leased more space with Powers for offices of the Board of Treasury.

The three years the Department of Foreign Affairs worked out of this building marked some of the busiest in early American foreign relations. Jay and his compatriots strove to enforce the Treaty of Paris signed on September 3, 1783, which ended the American Revolution and formally recognized the United States as an independent nation. They also ensured commercial treaties with the Netherlands and Sweden signed in 1782 and 1783 were carried out. A commercial treaty with Prussia was signed in September 1785 and a diplomatic treaty with Morocco to end pirate seizures of American vessels in the Mediterranean Sea was signed in June 1786. Further negotiations occurred with Spain regarding the boundary of West Florida and control of the Mississippi River, and with France regarding the functions and privileges of consuls in the U.S. and France. The three departments were tenants until May of 1788.

Peacetime activities of the Department of War, lead by Secretary Henry Knox, centered around the recruitment, outfitting, and maintenance of soldiers to protect the western territories between the Appalachian Mountains and Mississippi River.

The Board of Treasury offices including the Comptroller, Register Auditor, and Clerks, administered the daily financial activities of the government during the Confederation period. These activities included the repayment of public debt—at the time, some $10 million in foreign loans, $100 million in state loans, and loans from individual citizens—the equivalent of billions of dollars today. Clerks were responsible for the fiscal transactions and accounting of the national government. They also handled back pay for soldiers and the repayment of expenses incurred by officers.

In 1788, Powers leased the Tavern to John Francis who returned it to its tavern function. Dances and lectures were held in the Long Room. Groups such as the New York Society of the Cincinnati, the Bar Association, and the Society for Arts and Agriculture met at the Tavern. It was the official polling station for the Dock Ward in 1789. A year later, the Supreme Court dined at the Tavern to celebrate its opening.

The Tavern was at the center of a blossoming city, despite the 1790 Congressional approval to move the capital from New York City to present day Washington, D.C. In the years between 1783 and 1786 the population of New York City increased by 36% or 38,500 people. Direct trade with China began.

1795-1900

Powers sold 54 Pearl Street in 1795 to Dr. Nicholas Romaine. Under Romaine’s ownership, Mrs. Orcet, a widow, ran the building as a boarding house until 1800. During Orcet’s management there was an alleged murder. Ballerina Anna Gardie, who was living with her husband at the 54 Pearl Street boarding house was murdered in 1798. Her husband was also found dead from stab wounds; the coroner ruled it a murder/suicide.

Throughout the 1800s, 54 Pearl Street was run predominately as a boarding house with a bar on the first floor. Boarding houses were the housing solution for the large number of single men and young families that came to the City for work. In 1800, Orcet was replaced by Daniel Coughlen who opened a grocery store and tavern. That same year Romaine sold the building to builder, John Moore.

As ownership continued to change, the building’s history was never forgotten. 54 Pearl Street continued to be a gathering place for Patriots. On July 4, 1804 under the management of David Ross, the Society of Cincinnati held a meeting at 54 Pearl Street. Aaron Burr and Alexander Hamilton attended this meeting, which was held a week before their famous duel.

As the City continued to grow, so did the area around 54 Pearl Street. Between the years of 1827 and 1833 eleven other buildings on the block were built.

In 1832, 1837, and 1852, the building suffered serious fires. After each fire, the owner rebuilt and added modern additions. By the end of the 19th century the building bore little resemblance to the original structure. Two new floors and a flat roof were added. Upper floors were each divided into thirteen bedrooms and one toilet to accommodate boarders.

In 1883, the Sons of the Revolution℠ in the State of New York, Inc. was founded in the Long Room on the centenary of Washington’s farewell speech.

The building was always recognized as the famous Fraunces Tavern. The proprietors would affix signs to the masonry stating “Fraunces Tavern.” In 1890, the first floor was dropped to street level and the exterior was remodeled with cast iron and glass storefronts. The original timbers were sold as souvenirs.

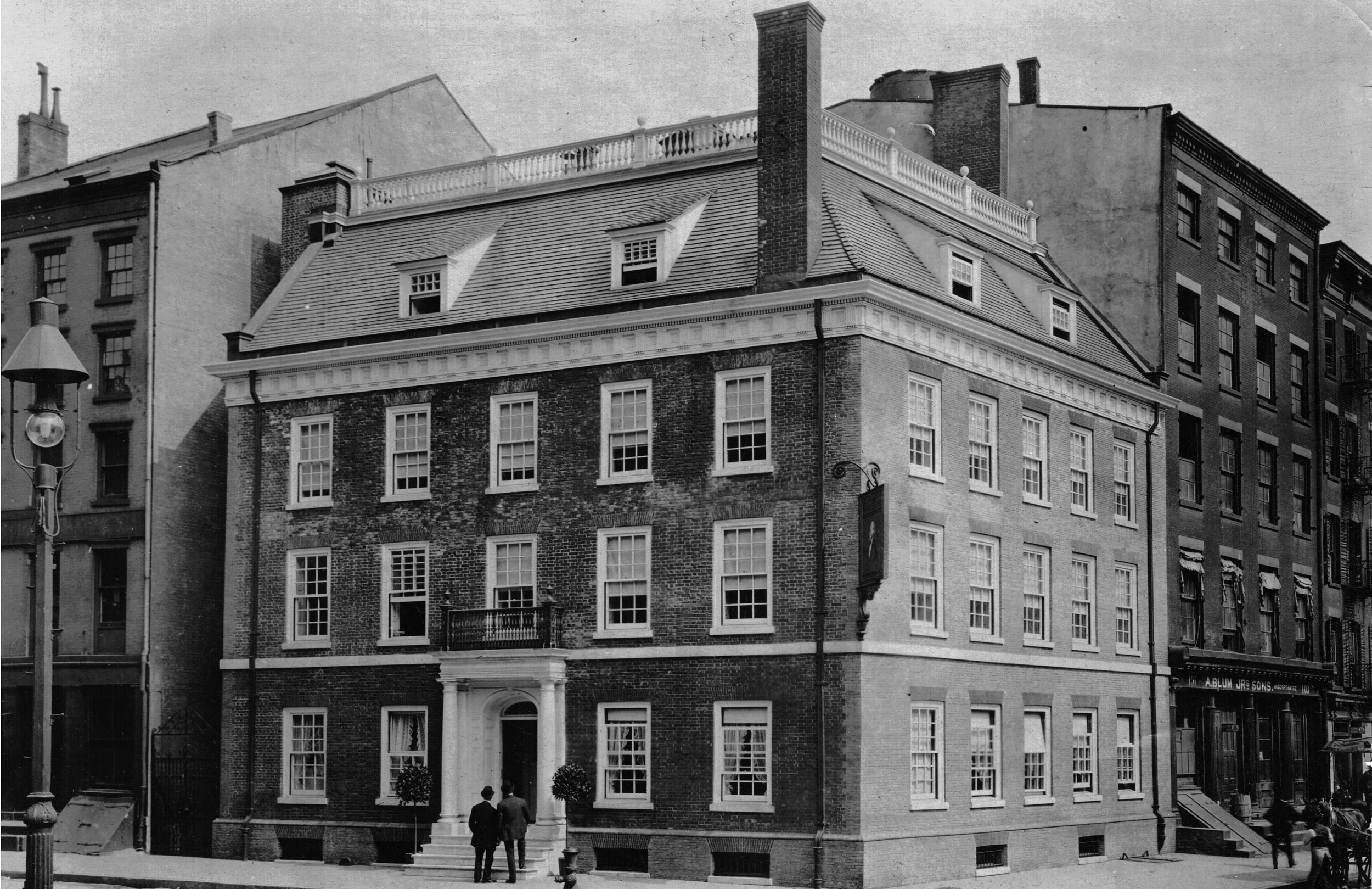

54 Pearl Street about 1888

1900-Today

The growing City was running out of building space. Old buildings were being replaced with new ones. In 1900, when 54 Pearl Street was threatened with demolition, the Daughters of the American Revolution with the aid of the Honorable Andrew H. Green, founder and president of the Society for the Preservation of Scenic and Historic Places, came together to try and save 54 Pearl Street for preservation. This committee was the nucleus of the later American Scenic and Historic Preservation Society. For several years, they attempted to purchase the building, but were refused by the owners.

The City got involved with saving 54 Pearl Street. To prevent the owners from destroying the building, the City of New York exercised its rights of eminent domain and designated it as a park in 1903. The following year the owners agreed to sell the property to the Sons of the Revolution℠ in the State of New York, Inc (SRNY). The City rescinded its park designation and the SRNY took title in July.

The goal of the SRNY was to restore 54 Pearl Street to its 18th century appearance and reopen it as a public museum and restaurant. In 1905, William H. Mersereau, an architect from Staten Island, was hired to head the restoration. He did extensive research and site analysis, but could not locate any image of the building prior to the first fire, which had significantly changed its appearance.

54 Pearl Street during 1906 restoration

Decades of modernization were stripped, starting with the cast iron facade. The deconstruction of 54 Pearl Street revealed red bricks on the Pearl Street side and yellow bricks on the Broad Street side. A definite difference could be seen in the older bricks and mortar of the second and third floors compared to that of the fourth and fifth levels. The south wall of the fourth story revealed the old roof line, which helped Mersereau determine the roof’s original slope.

When restoration was completed in 1907, the building was dedicated and opened as a Museum and Restaurant on December 4, the anniversary of Washington’s Farewell to his officers. The Restaurant was managed by Emil Westerburg.

By the 1960s, Fraunces Tavern grew to include four surrounding buildings. In 1965, 54 Pearl Street was designated as a New York City Landmark and in 1977 the entire block was designated as an Historic District on the National Register of Historic Places.

December 4, 1907 - Grand Opening of Fraunces Tavern

The Sons of the Revolution℠ in the State of New York, Inc. still own 54 Pearl Street, operating the Museum on the second and third floors, while leasing the first floor to a tenant who operates the Restaurant. The Museum sees over 25,000 annual visitors and is open seven days a week!

*Over the years, the Fraunces Tavern building has had a number of addresses. For much of the 18th century it was 49 Grand Dock Street. In 1794 it became known as 56 Pearl Street. To ease confusion, the building is referred to consistently on this site by its present address, 54 Pearl Street.