Love in the Time of Revolution

by Mary Tsaltas-Ottomanelli

In honor of Valentine’s Day, Special Programs & Engagement Manager Mary Tsaltas-Ottomanelli explores the art of letter writing between some of history’s most notable 18th century couples and offers practical tips for readers to do the same.

Dear Reader,

With each approaching February, I reflect on the relationships of some of my favorite revolutionary couples and the love and affection they shared through such turbulent times. The origins of Valentine’s Day are a little unclear to this historian, though it dates back to Ancient Rome and possibly three different Saint Valentines who were martyred. Needless to say, I’m glad the holiday we celebrate today involves exchanging more chocolate than violence. Although something tells me none of the founding fathers and mothers featured below would have turned down heart-shaped chocolate...

Our modern traditions of Valentine’s Day were not the same as they were in the 18th century, but writing letters to loved ones remains. With quill and ink, these couples maintained constant communication through the hardship and separation of war, overseas diplomacy, and serving in the highest seats of our emerging nation. Their letters contain notes of respect, empathy, longing for returns, and of course, some cheeky, playful banter.

Revolutionary Couples

Our favorite founding fathers and mothers were quite the romantics in the 18th century. Often separated for months at a time during the Revolutionary War, the only way to communicate was through handwritten letters with messages of love, longing, and endearment.

George and Martha Washington

On March 16, 1758, a young George Washington traveled thirty-five miles to Martha Dandridge Custis' home in New Kent County in an attempt to win the attention of one of the most beautiful and wealthiest women in Virginia. George visited Martha once again on March 25. A spark was lit between the two, and within months the couple was set to be married.

The Marriage of Washington to Martha Custis, by Junius Brutus Stearns, 1849, courtesy of Virginia Museum of Fine Art.

The widow Custis stood in a uniquely powerful and independent - rarely seen for women during the 18th century. After the death of her first husband, Daniel Parke Custis, she took control over the nearly £40,000 estate (nearly $8 million today). Martha did not need to marry for financial security, but rather for a love match. She found that in the young Washington who was most known for his bravery during the French and Indian War. On January 6, 1759, Martha Dandridge Custis married George Washington on Twelfth Night, traditionally an evening of celebrations. For the majority of their nearly forty-year marriage, the couple sacrificed their time together to help support the new nation.

After George died in 1799, Martha burned all of the couple's correspondences to protect the couple's privacy. As a result, less than a handful of letters between the couple exist today.

One letter was found tucked away in a desk drawer by one of Martha Washington's granddaughters. Dated June 23, 1775, George wrote to Martha as the army was moving from Philadelphia to Boston. "I could not think of departing from it without dropping you a line; especially as I do not know whether it may be in my power to write again till I get to the Camp at Boston." In the short letter, he goes on to write, "I retain an unalterable affection for you, which neither time or distance can change, my best love to Jack & Nelly, & regard for the rest of the Family concludes me with the utmost truth & sincerity." He signs the letter 'your entire,' an intimate and romantic sign-off to a letter in the 18th century.

To read more about the remaining letters between George and Martha click here.

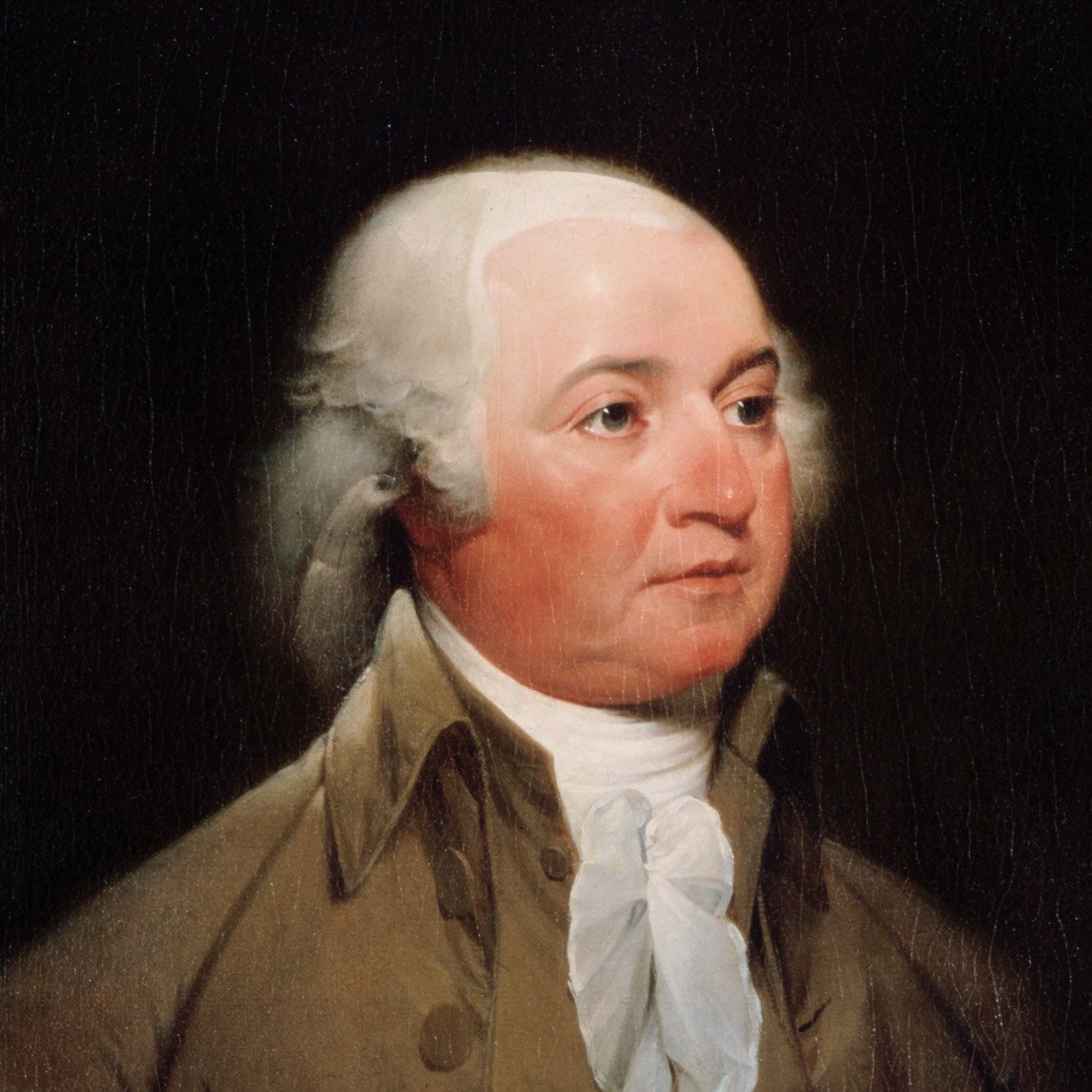

John and Abigail Adams

John and Abigail Adams were another couple that sacrificed many years of their marriage to support the cause of liberty. Most of their marriage was spent apart from each other. The couple viewed each other as intellectual equals and shared over 1,000 correspondences over the course of their marriage, which were not destroyed. These letters give us an intimate look into one of the most interesting and passionate couples of the 18th century. Their letters show a couple who loved and respected each other, speaking as equals and partners during difficult times. They were not afraid to speak their minds, as Abigail once famously wrote her husband to 'Remember the ladies' and women's equality in the fight for independence.

Letter from John Adams to Abigail Smith, 4 October 1762. Courtesy of Massachusetts Historical Society.

The two were playful and romantic in their letters by calling each other special nicknames. Early in their relationship, the couple addressed each other as "Diana," the Goddess of the Moon, and "Lysander," the Spartan hero that ended the Peloponnesian War. She called him "My Dearest Friend." He called her "Miss Adorable" and his "Heroine," who sustained "with so much Fortitude, the Shocks and Terrors of the Times." They were not shy about their affection for each other. In a 1762 letter, John wrote to Abigail, "to give the bearer as many kisses and as many hours of your company after 6 o'clock as he shall please to demand and charge them to my account."

If you’d like to learn more about the enduring relationship of John and Abigail, check out the book First Family: Abigail and John Adams by Joseph Ellis.

Henry and Lucy Knox

Lucy Flucker met Henry Knox when she visited his bookstore in Boston in 1773. Almost immediately, the couple became inseparable - at first writing letters about the books they read and then letters referencing their love for each other. At the time, Henry Knox maintained a respectable bookstore while Lucy was the daughter of a high-ranking British official. Her decision to court the Patriot leaning Knox was met with disapproval from her Loyalist family, but the couple continued their courtship. Lucy disobeyed her family's wishes and wed Henry on June 16, 1774, in an intimate ceremony above his bookshop. The couple escaped the city after the Battles of Lexington and Concord, with Knox enlisting in the Continental Army shortly after.

Nearly a complete collection of their correspondences during the Revolutionary War survive today. Knox's letters to Lucy during the war detailed accounts of the struggles of warfare, mentioning battles, troop movements, and even some intelligence on the British. One of their letters details Knox's orders to cross the Delaware River in December 1776. These letters provide a realistic perspective of military couples during the Revolutionary War.

Lucy Flucker Knox to Henry Knox [Boston, Massachusetts, May 1777]. Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, GLC050895.

These letters were a lifeline to the couple who were separated on and off for nearly eight years. In a letter to Henry in 1777, Lucy writes from their home in Boston about her current situation getting over an illness. Henry has asked what she does throughout the day, where she tells him, "it is my love so barren of adventures and so replete with repetition that I fear it will afford you little amusement - however such as it is I give it you." She also speaks about the family she fears will never speak to her again after marrying Henry and siding with the Patriot cause. What is visible is Lucy's (understandable) insecurities brought by the time apart from her 'dear Harry' and their strong bond to each other. She writes, "I love you with a love as true and sacred as ever entered the human heart - but from a diffidence of my own merit I sometimes fear you will Love me less - after being so long from me - if you should may my life end before I know it - that I may die thinking you wholly mine."

More about the Knox’s marriage and their letters can be found in The Revolutionary War Lives and Letters of Lucy and Henry Knox by Philip Hamilton.

The Art of Etiquette and Courtship

The rise of American print culture during the mid-18th century saw an immediate increase in books, newspapers, and pamphlets relating to the etiquette around courtship for young people. The books reflected the growing social changes brought on by the Enlightenment era. Women specifically ushered in more progressive ideas about autonomy, rationality, and the decision to marry for love than economic or social standing. With more educational access, women began advocating for equal status in the patriarchal society by choosing their husbands and romantic partners. This influence is seen with the publication of Jane Austen and Hannah Webster Foster novels.

One of the most popular etiquette books was The New Academy of Compliments, published in 1799. The book contains information for both men and women on complimenting nearly every person they would interact with in almost every social situation— from a letter of kindness to a friend and how a gentleman addresses a rival.

Benjamin Franklin wrote a book with courtship advice, titled A Reflection on Courtship and Marriage, in 1746. The book acts as a modern-day advice column, with "Old Batchelor" (assumed to be Franklin) answering questions about love and courting. Although most of the advice "Old Batchelor" gives is quite [raunchy], one piece of advice still stands today:

'TIS a common Saying, that Love begets Love; that is not always true. But where there is any Similitude of Minds, Sentiments of Friendship, will beget Friendship.

LET us then take every Opportunity of testifying our Esteem and Friendship: Court the Understanding, the Principles of Thought, and conciliate them to our own.

HEREBY we shall as it were enter into the Soul, and take Possession of all its Powers; this should be the Ground-work of Love, this will be a vital Principal to that, and make our Concord as lasting as our Minds are unchangeable.

Writing to Your Beloved

So Dear Reader, it is time I ask you to write a letter to your beloved. With pen and paper, following your heart and without the use of emojis. Follow the foundations of these couples and etiquette books. I share with you some of my favorite phrases of affection for you to derive inspiration from:

“I retain an unalterable affection for you, which neither time nor distance can change.” — George to Martha Washington June 1775

“Should I draw you the picture of my Heart, it would be what I hope you still would Love; tho it containd nothing New; the early possession you obtained there; and the absolute power you have ever mantaind over it; leaves not the smallest space unoccupied” — Abigail to John Adams, December 1782

“You engross my thoughts too entirely to allow me to think of any thing else—you not only employ my mind all day; but you intrude upon my sleep. I meet you in every dream—and when I wake I cannot close my eyes again for ruminating on your sweetness.” — Alexander Hamilton to Elizabeth Schuyler, October 1780

Your Most Humble and Obedient Servant,

Mary