The Last Days of Nathan Hale

by Mary Tsaltas-Ottomanelli

Solider, spy, and Patriot, Nathan Hale's death is regarded as one of American history's greatest patriotic moments and launched him into martyrdom, but most of his life is largely shrouded in mystery.

The Early Years

Nathan Hale was the sixth of the Hale children, born on June 6th, 1755, into a respectable Puritan family in Coventry, Connecticut. Hale's early life was spent much like children living in the countryside in the 18th century – fishing, hunting, and chores to maintain the homestead.

Illustration of Yale University at the time Hale attended.

image courtesy of Yale University Library

In 1769, Hale and his brother Enoch left Coventry for higher education at Yale University, where the curriculum focused more on classics and religion. Hale's classmates spoke highly of him: "No young man of his years put forth a fairer promise of future usefulness and celebrity; the fortunes of none were fostered more sincerely by the generous good wishes of his superiors."[i] He was a member of Linonia, a secret literary fraternity, where he met Benjamin Tallmadge, the future leader of the Culper Spy Ring.

A Schoolmaster Observes Political Unrest in the Colonies

Like other coastal towns, New Haven, Connecticut was a hotbed of political discourse. By the time Hale graduated from Yale in 1773, the political atmosphere in the colonies had grown tense. Colonial resentment continued to rise with the passing of each new tax introduced by British Parliament, especially in conjunction with the increased military presence in New England.

This page of the college records for the winter quarter of 1770-71 shows that everyone paid 12 pounds for tuition. Room rent was 1 pound 6 shillings and "contingent charges" were 1 pound 4 shillings. Both Hales also were also charged "punishment" fees for unspecified mischief: Hale 1 [Enoch] 3 pounds and Hale 2 [Nathan] 4 pounds. Courtesy of Yale University Library

In the spring of 1774, Hale settled into his new role as a schoolmaster of the Union School in New London, Connecticut. Around this time, British General Thomas Gage and thousands of troops to sailed to occupy Boston.

Immediately, Bostonians, including Sons of Liberty member Samuel Adams, organized the Committee of Correspondence. On September 8th, 1774, Hale wrote to his brother Enoch about the political unrest, stating "no liberty-pole is erected or erecting here: but the people seem much more inspired than they were before the alarm. Parson Peters of Hebron, I hear, has had a second paid visit to him by the sons of liberty in Windham."[ii]

Liberty poles first appeared in the colonies to protest the Stamp Act, and quickly became a symbol for the Sons of Liberty. By 1775, war was beginning in New London - cannons moved into the port and pointed out into the harbor, and the Hartford legislature assembled military divisions.

A Call to Serve

New Londoners received news of the Battles of Lexington and Concord on April 22nd by way of a messenger en route to New York. A mandatory town meeting was called for and took place that evening at Miner's Tavern; it was an official call for men and arms. After some discussion, it was decided that a volunteer company, founded the previous winter and led by Captain William Coit, was to leave at the break of dawn. This was the moment Hale heard the call to serve his country.

After volunteering to march to Boston, Hale ended his speech with, "let us march immediately and never lay down our arms until we obtain independence."[iii] Hale's use of the word independence in 1775 was still very radical and disfavored by most colonists. Hale knew, even before our founding fathers, that liberty was imminent.

Benjamin Tallmadge as a dragoon, by John Trumbull, c. 1783. Source: Memoir of Colonel Benjamin Tallmadge. Fraunces Tavern Museum.

Hale enlisted in the Continental Army after receiving a letter from his close friend and schoolmate, Benjamin Tallmadge, on July 4th, 1775. Tallmadge had returned home from the standoff between British and Patriot forces at Cambridge. He wrote to Hale about the importance of enlisting in the Continental Army, noting, "Was I in your condition… I think the more extensive Service would be my choice. Our holy Religion, the honour of our God, a glorious country, & a happy constitution is what we have to defend."[iv]

On July 1st, 1775, Nathan Hale accepted a commission as a lieutenant in Colonel Charles Webb’s Connecticut Seventh Regiment. Hale’s high-ranking title was the result of his high level of education from Yale.

For the duration of summer, Hale prepared his brigade for their march to Boston, training new recruits, and guarding the Connecticut coastline in case of enemy attack. Hale wrote to his father, Richard, about his decision to join the army, saying, "A sense of duty urged me to sacrifice everything for my country." [v]

Connecticut's Seventh Regiment left for Boston in September 1775 to join some 30,000 other troops. By November, the thrill and excitement of impending battle began to wane and Hale grew restless. According to Life & Death, "With nothing but time on his hands, he marked the days and nights by playing checkers, exercising, and marching his men in proper formation, keeping them disciplined, in shape, and ready to engage."[vi]

Nathan Hale, a captain in the nineteenth regiment of foot command by Colonel Charles Webb. Signed by John Hancock. Courtesy of the Yale University Library.

Hale showed a lot of promise in the early years of the war. Elisha Bostwick, a fellow officer, described Hale: "His mental powers seemed to be above the common sort, his mind of a sedate and sober cast, & he was undoubtedly pious."[vii]

On November 19th, 1775, while Hale bided his time waiting for action, the Continental Congress motioned a plan for espionage. Congress created the Committee of Secret Correspondence "for the sole purpose of corresponding with our friends in Great Britain and in other parts of the world." [viii]

Secret agents were employed abroad who "conducted covert operations, devised codes and ciphers, funded propaganda activities, authorized the opening of private mail… established a courier system, and developed a maritime capability apart from that of the Navy." This laid the foundation for the Modern day CIA.

The twenty-one-year-old commander of an eighty-men company was sent to Brooklyn during the Battle of Long Island, but not stationed on the front-line. Instead, they "witnessed from afar the disaster that befell Washington's soldiers at the hands of the best army in the world." [ix] Hale, frustrated after watching a major battle of the war and unable to fire his musket, sought to transfer units.

Thomas Knowlton’s Rangers

After the Battle of Long Island on August 27th, 1776, General Washington was in desperate need of intelligence on the enemy – he wanted to know about troop movements, supply numbers, and General Howe's next move. The Patriots recognizes that their best chance of winning this war lied in a strong offense, rather than defense. They needed to know their enemy's next move before it was too late to react.

Hale transferred into Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Knowlton's regiment, which focused on carrying out reconnaissance missions. Composed of about a hundred and fifty men, Knowlton's Rangers was the first organized group of elite soldiers whose focus was discreetly gathering intelligence.

Knowlton requested a ranger to cross over British lines and gather intelligence on the enemy. Hale was the only soldier to volunteer."I think I owe it to my country, the accomplishment of an object so important, and so much desired by the commander of her armies – and I know of no other mode of obtaining the information, than by assuming a disguise and passing into the enemy's camp," he wrote. [x]

Although he’d been enlisted in the army for over a year, Hale spent more time writing muster rolls than firing his musket, and he was eager to fight.

Knowlton’s first choice for the mission wasn’t Hale, but Officer James Sprauge who refused. The idea of being an agent of espionage in the 18th century was largely frowned upon – in a time where honor, morals, and integrity were the highest regarded forms of decency, being a spy was Seen as ungentlemanly.

Hale's ability to recognize and draw scaled fortifications of British forts and encampments made him a great choice for this mission, however, he was probably not the best candidate for a spy. His educational experience and strong religious beliefs emphasized integrity and honor, thus hindering his ability to perform the duties required of a spy.

Hale spoke with a friend, Captain William Hull, about his mission before he left. According to Hull, he tried to talk Hale out of carrying out the mission and facing what he considered a guaranteed death.

To be a good spy, you need to be a good liar – a skill Hale likely hadn’t perfected. Hale also Couldn’t help but carry himself like a soldier and did not easily blend into a crowd. He had a powder burn on his cheek, a most unusual and suspicious scar for a schoolteacher.

Hull didn't believe Hale was right for the mission, writing that it was "not in his character; his nature was too frank and open to deceit and disguise, and he was incapable of acting a part equally to his feelings and habits."[xi]

Hale Begins His Mission

Simeon De Witt, A Map of the State of New York, 1802 First American map of Long Island to improve on British revolutionary war era maps, courtesy of Library of Congress

On September 15th, 1776, Hale embarked on his mission, escorted through the first portion by Sergeant Stephen Hempstead. The plan was for Hale to complete a four-day journey to Howe's encampment in Brooklyn and to speak with Tory residents and British soldiers, gathering any information about their movements along the way.

The Long Island Sound was a very hostile and dangerous stretch of water, packed with warships and privateers. About fifty miles from where the journey began in Norwalk, Hale found safe passage aboard the armed sloop Schuyler. As he traveled to Brooklyn, Hale observed the movement of supplies and troops heading westward.

It is important to note that the mission hale was sent in was doomed from the start; he was likely given little to no instructions before his departure. He traveled with his Yale diploma, which gave away his name and botched his alias. And, although Hale was a school teacher in New London, it's unclear whether or not he spoke fluent Dutch.

Hale set out with a high chance of being recognized as a Continental Soldier (five of the eight Hale children enlisted as Patriots). There is no record of how or what specific kind of data Hale was to collect, the method he would employ for doing so, or even a plan for escape. Hale was truly on his own once he landed in Long Island.

Hale Meets Roger’s Rangers

While Hale scoured Brooklyn for information, Major Robert Rogers searched for defectors from the British Army.

Robert Rogers - commandeur der Americaner. United States, 1778

courtesy of the Library of Congress

Robert Rogers was born and raised in New Hampshire in the 1740s and enjoyed exploring the region’s wilderness. Rogers enlisted as a captain in a New Hampshire regiment during the French and Indian War that was notorious for its aggressive and brutal tactics.

At the outbreak of the Revolutionary War, Rogers, essentially searching for the best deal from whoever offered it, tried to solicit his scouting talents to the Whigs and Patriots. Both sides were equally suspicious of his loyalties.

By August 6th, 1776, Rogers secured a commission by British Commander Howe to raise a battalion known as the Queen's American Rangers. Rogers and his Rangers took the military's Most undesirable jobs – transporting and guarding prisoners of war, espionage, and even carrying out assassinations. Rogers was once described "as subtil & deep as Hell itself… a low cunning cheating back biting villain."[xii]

Rogers had dozens of paid informants in both Long Island and Connecticut who provided information on everything from Continental troop and supply movements, to suspicious outsiders asking suspicious questions. Rogers received a tip that the Schuyler has sailed into Long Island and dropped someone off before quickly sailing away in the middle of the night.

Rogers was able to track down Hale on September 19th, trailing him for hours. It was that day that, Unfortunately, Rogers caught Hale scribbling notes after passing a barracks or detachment of soldiers.

Nearing the end of his mission, Hale rented out a room in a roadside tavern and expected to be picked up by the Schuyler in the morning. At some point, as Hale dined, Rogers casually walked in, sat down next to him, and started up a conversation. As they spoke of the war, Rogers fabricated lies about being an American behind enemy lines, complaining about being detained by Tories.

"Representation du Feu terrible a Nouvelle Yorck" The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1776.

As the two men continued drinking and talking, Rogers gained the trust of the young spy – witnesses claim they two men toasted to Congress's health. By the end of the evening, Hale admitted he was on a mission from General Washington to gather information about General Howe.

That night, there were two fiery forces—one engulfing Hale and the other ravaging the Bowery. Sometime in the night on September 21st, a fire broke out at the Fighting Cocks Tavern that quickly spread, burning down nearly 500 structures—almost a third of the city.

Rogers needed more proof that Hale was a spy before he could take any action: he needed Hale to confess in front of witnesses. Rogers invited Hale to breakfast the next morning.

According to Consider Tiffany's diary, "the time being come, Capt Hale repaired to the place agreed on, where he met his pretended friend, with three or four men of the same stamp." [xiii]

As Hale spoke to what he thought were fellow patriots, he never once realized that he was caught in a trap. Rangers in civilian clothing were sitting at the surrounding tables, and more circled the tavern in case Hale attempted to escape. Rogers gave the signal, stood, and proclaimed Hale a spy. The Rangers quickly encircled him.

Hale was dragged out of the tavern with shackles around his arms and legs while loudly proclaiming his innocence. Accounts from onlookers claim Hale shouted that he was a deserter who was disgusted with the cause and did not want to enlist in the Continental Army. Placed on the Halifax, Hale was taken to New York City. It was time to face General Howe.

Hale was delivered to General Howe along with a stash of notes and drawing discovered on his person by the Rangers. Almost immediately, Hale gave up his name, rank, and his goal of crossing into British lines.

Rogers also brought a witness to offer testimony that he recognized Hale. General Howe signed Hale's death warrant and his execution scheduled for the next day. Hale's request for a chaplain or bible were both rejected.

The Hanging of a Patriot Spy

"Nathan Hale." The New York Public Library Digital Collections.

Hale spent his final hours with Howe's chief engineer, Captain John Montresor, deciphering his notes and drawings. Reflecting on that morning, Montresor wrote, "He was calm, and bore himself with gentle dignity, the consciousness of rectitude and high intentions."[xiv]

Hale asked for two things that morning – quill and paper – to write two letters: one to His brother Enoch, and Another to his commanding officer Thomas Knowlton. Later that morning, Hale walked to an apple orchard somewhere around present-day sixty-sixth Street and third avenue in New York City. One witness noted that Hale “walked with the grace and stateliness of a man carrying out the will of his people, the will of his God." [xv]

Howe’s orderly book noting Hale’s execution.

His hands were tied behind his back and clothed in a white winding-sheet, which would be used to cover his corpse. A few guards followed the procession, as well as a cart loaded with pine boards for his coffin. There was no formal ceremony for Hale's execution. "Nathan stood proudly, head tilted skyward, posture firm, hands tied behind his back."[xvi]

Later that day, Howe noted Hale's death in an orderly book: "A spy from the enemy (by his own full confession) apprehended last night, was this day executed at 11 oClock in front of the Artillery Park."[xvii]

Author's note: Although "I only regret that I have just one life to lose for my country" is synonymous with Hale's name, I err on the side of caution for relaying these words. Historians today do not believe these were Hale's last words and that this quote has been dramatized by friends and family to keep Hale's legacy in the forefront. It is noted that Cato was an important play that Hale and Tallmadge were heavily influenced by during their time at Yale. Hale's infamous last words are believed to be derived from Joseph Addison's 1713 play Cato: A Tragedy, which dramatizes the last days of Roman Senator Marcus Poricus Cato (94-46 BCE), who was an "exemplar of republic virtue and opposition to tyranny.[xviii] Hale's words are paraphrased from scene II, act Four -- "How beautiful is death, when earn'd by virtue! / Who would not be that youth? What pity is it / That we can die but once to serve our country." This was not the only Revolutionary figure inspired by Cato; Patrick Henry's 'Give me Liberty or give me death' was influenced by the line "It is not now a time to talk of aught/But chains or conquest, liberty or death" in the same scene.

The Aftermath

The Hale family knew something was wrong when they didn’t hear from Nathan for almost a month. Enoch wrote in his diary about rumors circulating in Coventry that "Capt. Hale, belonging to the east side of Connecticut River, near Colchester, who was educated at College, was seen to hang in the enemy lines at N York being taken as a spy.” [xix]

Enoch rode into the White Plains encampment on October 26th to speak with Colonel Charles Webb's regiment Intending to verify the rumor. Webb confirmed Enoch’s worst fears: his brother had been executed.

Webb relayed that he was notified on September 22nd by Montresor that "Nathaniel Hale was hanged for a Spy… That being suspected by his movement… [that] he wanted to get out of N York, was taken up & examined by the Gen & some minutes being found on him orders were immediately given that he should be hanged." [xx]

This tragic loss was kept quiet in an effort to not heighten the already low morale at camp. Hale's death received no formal announcement.

On June 4th, 1777, nine months after his death, Hale's belongings were returned to his family at Coventry farm. The trunk had "uniform, army diary, receipt book, camp basked, a book of muster rolls, his captain's commission, several letters."[xxi]

The two letters Hale wrote the morning of his execution never made it to their intended recipients. Here is the last known surviving later Hale wrote to his brother, Enoch, dated August 20th, 1776, right before the Battle of Brooklyn. Read more about the letter in the Digital Exhibition, Valuable.

Nathan Hale’s Legacy

Hale's first mention in literature came after the war in 1799 in Hannah Adams' History of New England, with a brief account of Hale's life. The revival of Hale's service was spearheaded by Antiquarian George Dudley Seymour, who purchased the Hale Homestead in Coventry in 1914.

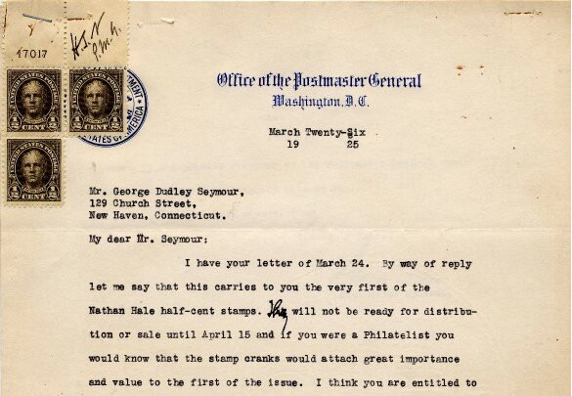

Letter from Office of the Postmaster General to George Dudley Seymour with the first copies of the Nathan Hale Stamp. Courtesy of the Yale University Library

Seymour went on to write dozens of books, pamphlets, essays, and even a play highlight Nathan Hale's life and legacy. Seymour led the campaign for a Nathan Hale stamp in 1925. The new half-cent denomination used the Bela Lyon Pratt statue for the engraving and endorsed with "H.S.N." By 1930, more than 2.6 Hales were issued.

Each year the Sons of the Revolution in the State of New York commemorate Hale's life with a ceremony and wreath-laying in front of the Nathan Hale Statue in New York’s City Hall Park. The eight-foot bronze statue was designed by twenty-six-year-old Frederick MacMonnies, who won the Nathan Hale Memorial Competition.

On November 25th, 1893, the 110th anniversary of the Evacuation of British troops in New York City, the Sons of the Revolution unveiled the statue of Nathan Hale at City Hall. At the time, it was believed that Hale was hung in the area around City Hall.

Bibliography

Daigler, K. A. (2015). Spies, Patriots, and Traitors: American Intelligence in the Revolutionary War. Washington D.C.: Georgetown University Press.

Huston, James. “Nathan Hale Revisited A Tory's Account of the Arrest of the First America Spy.” Library of Congress, July 2003, loc.gov/loc/lcib/0307-8/hale.html.

Phelps, M. William. Nathan Hale: The Life and Death of America's First Spy, University Press of New England, 2014.

Rose, Alexander. Washington's Spies: The Story of America's First Spy Ring. New York: Bantam Books, 2006. Print.

“Secret Committee of Correspondence/ Committee for Foreign Affairs, 1775–1777.” Office of the Historian , history.state.gov/milestones/1776-1783/secret-committee.

Footnotes

[i] Life and Death, 21

[ii] Life and Death, 53

[iii] Life and Death, 68

[iv] Spies, Patriots, and Traitors, 98

[v] Life and Death, 76

[vi] Life and Death, 97

[vii] Life and Death, 81

[viii] Secret Committee of Correspondence

[ix] Washington’s Spies, 11

[x] Life and Death, 142

[xi] Spies, Patriots, and Traitors, 100

[xii] Washington’s Spies, 19

[xiii] Life and Death, 179

[xiv] Life and Death, 188

[xv] Life and Death, 191

[xvi] Life and Death, 192

[xvii] Washington’s Spies, 32

[xviii] Cato < https://www.mountvernon.org/library/digitalhistory/digital-encyclopedia/article/cato/>

[xix] Life and Death, 197

[xx] Life and Death, 215

[xxi] Life and Death, 224