The Battle of Trenton: A Turning Point in the American Revolution

By Armonee Wilkins

Programs & Events Coordinator Armonee Wilkins explores how Washington’s bold crossing of the

Delaware and the Continental Army’s victory at Trenton transformed revolutionary momentum and revived the Patriot cause.

Courtsey of the Metropolitan museum of art

During the Revolutionary War, the New Year took on a new significance; it became a sign of hope for liberty. In December 1776, General Washington, along with his soldiers, gave up their Christmas holiday to sail across the Delaware River through a winter storm, to fight for the new beginnings they longed for. This bold maneuver led to the Battle of Trenton on December 26, 1776, which supported and fueled the fight for freedom.

Morale was at an all-time low. The winter of 1776 was a trying time for the Continental Army, after several defeats such as the Battle of Long Island and the loss of Fort Washington. George Washington was forced to retreat from New York City, which was the Continental Army Headquarters during the War, as the British were in control of Manhattan Island.

Washington’s forces were declining due to enlistments set to expire, causing many Americans to believe the revolution was set to fail. They did not count on how ambitious Washington was – he refused to give up.

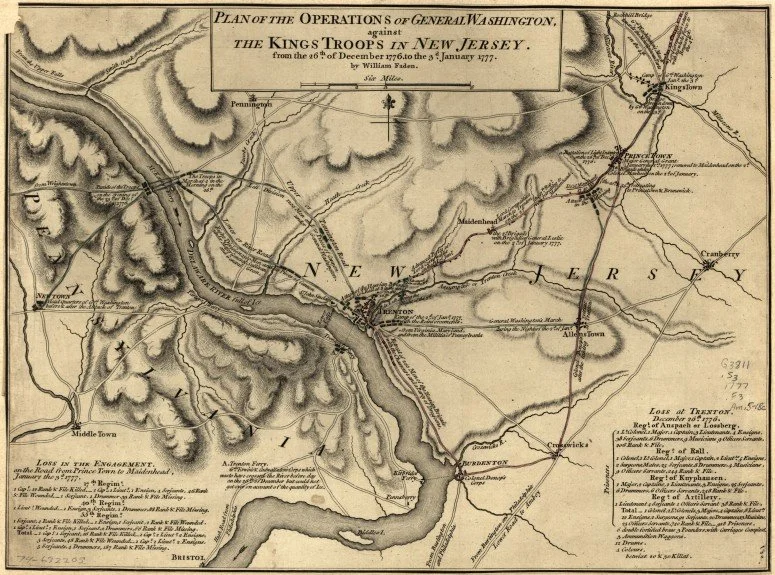

Plan of Operations of General Washington against the King's Troops in New Jersey by William Faden, 1777 (Library of Congress Geography and Maps Division)

Washington composed a risky plan to surprise the British, restock supplies, and raise morale, asking his men to give their faith in one last attempt [1]. The intent was to split the American army into three: Colonel Cadwalader led 1,800 troops near Burlington, New Jersey to stop the British from sending reinforcements to Trenton [2]. General James Ewing led 800 soldiers to the Assunpink Creek, to prevent enemy troops from escaping [3]. Lastly, Washington and his 2,400 soldiers were to march on Trenton and ambush the British garrison.

However, the initial plan failed quickly when a severe snowstorm forced Col. Cadwalader, Gen. Ewing, and their troops to turn back [4]. This meant Washington was down to 2,400 troops altogether. When they arrived on the outskirts of Trenton, Washington broke his remaining troops into two, having one group attack from the north and a second attack from the west, leaving the south as the only retreating option for the British.

Despite being underprepared and low on morale, the Continental Army fought hard, leaving the Americans victorious. The 1,500 British forces suffered 905 casualties, while out of the 2,400 Americans, there were only 5 reported casualties [5].

After winning the Battle of Trenton, Washington initially retreated to Pennsylvania, to regroup. However, on December 29th, he returned with his troops to occupy Trenton. General Cornwallis and his 8,000 soldiers tried to cross the Assunpink River to attack Washington’s forces in Trenton. However, after three failed attempts, they retreated with strong intentions to return the next day.

General Cornwallis kept his promise and renewed his assault on December 30; however, Washington was a few steps ahead. Washington kept approximately 500 of his troops at Trenton, making Cornwallis believe that he was closing in on Washington’s primary forces [6], while Washington secretly marched the rest of his troops to Princeton and closed in on the British garrison.

Even after the victory at Trenton, the problem of the American army’s expiring enlistments remained. On the 31st of December, Washington turned to his troops one final time, asking them to stay enlisted for six more weeks, with the promise of an extra ten dollars. Many of his men, moved by loyalty and conviction, chose to remain beyond their enlistment dates, standing steadfast in the face of uncertainty [7].

This victory of Washington’s appeal to the troops demonstrated the resilience and determination of the American soldiers, and the Battle of Trenton proved that the fight for independence was far from over, inspiring hope among the Americans and earning renewed support for the revolution both at home and abroad. Trenton remains a testament to the courage and strategic brilliance that defined the struggle for American independence.

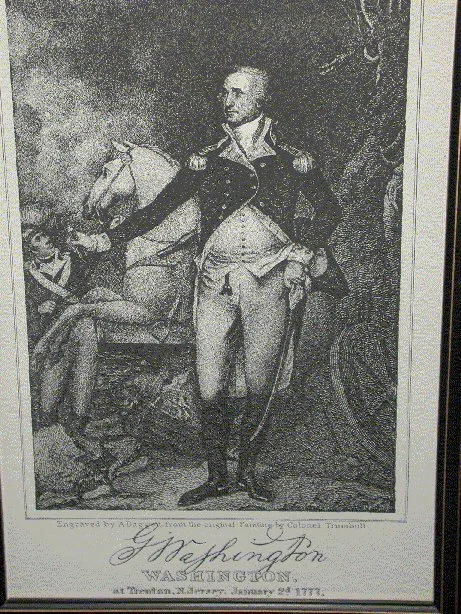

“Washington at Trenton, N. Jersey, January 2d, 1777” Credit to Fraunces Tavern Museum

Years later, on December 4, 1783, Washington delivered his farewell to his officers in the Long Room of Fraunces Tavern. The last of the British troops had evacuated the week before, and the war was won. In his farewell, Washington acknowledged his troops, especially those who stayed past their enlistment periods:

“With a heart full of love and gratitude I now take leave of you. I most devoutly wish that your latter days may be as prosperous and happy as your former ones have been glorious and honorable.” [8]

The gratitude that he expressed goes beyond the courage soldiers demonstrated, also encompassing their commitment to the nation. Washington echoed the spirit of resilience displayed at the Battle of Trenton. Where against all odds, his leadership turned the tide of the Revolution and inspired a nation to endure.

Today, that spirit of perseverance and sacrifice is preserved at the Fraunces Tavern Museum, where Washington’s story is not only remembered but grounded in place. The same Long Room in which he bade farewell to his officers stands as a physical reminder of the journey that began with desperate hope in the winter of 1776 and culminated in hard-won independence. Through the Museum’s Path to Liberty exhibition, a chronological, multi-year exhibition telling the history of the American Revolution from 1775 to 1783, visitors are invited to trace this arc of struggle, resilience, and resolve—from moments like the daring crossing of the Delaware and the victory at Trenton to the personal bonds forged between Washington and his soldiers.

Footnotes

[1]Washington Crossing the Delaware, Bill of Rights Institute.

[2]“10 Fact about Washington’s Crossing of the Delaware River”, George Washington’s Mount Vernon.

[3]“10 Fact about Washington’s Crossing of the Delaware River”, George Washington’s Mount Vernon.

[4]“The Battles of Trenton and Princeton” Stryker, p218-219,

[5] “Battle of Trenton Facts & Summary”, American Battlefield Trust

[6] Battle of Princeton, Mount Vernon.

[7] Washington Crossing the Delaware, Bill of Rights Institute.

[8] Memoir of Col. Benjamin Tallmadge, p63

References

American Battlefield Trust. “Battle of Trenton Facts & Summary.” American Battlefield Trust, American Battlefield Trust, 27 Jan. 2017, www.battlefields.org/learn/revolutionary-war/battles/trenton.

“Battle of Princeton” George Washington’s Mount Vernon, Mount Vernon, 2024, www.mountvernon.org/library/digitalhistory/digital-encyclopedia/article/battle-of-princeton#6. Accessed 19 Dec. 2024.

“Battle of Princeton (Jan. 3, 1777) Summary & Facts.” Totally History, 24 Jan. 2012, totallyhistory.com/battle-of-Princeton/.

“Crossing of the Delaware.” George Washington’s Mount Vernon, www.mountvernon.org/library/digitalhistory/digital-encyclopedia/article/crossing-of-the-delaware. Accessed 6 Dec. 2024.

Memoir of Col. Benjamin Tallmadge New York: T. Holman, 1858. p. 63 Selected Digitized Books

Stryker, William Scudder. The Battles of Trenton and Princeton. 1898.

Washington Crossing the Delaware, American Revolution, U.S. History, Strategic Military Movements, Leadership.” Bill of Rights Institute, billofrightsinstitute.org/essays/washington-crossing-the-delaware.

“10 Facts about Washington’s Crossing of the Delaware River.” George Washington’s Mount Vernon, Mount Vernon, 2024, www.mountvernon.org/george-washington/the-revolutionary-war/washingtons-revolutionary-war-battles/the-trenton-princeton-campaign/10-facts-about-washingtons-crossing-of-the-Delaware-river.