Fort Detroit: The Frontier of British Power and Native Diplomacy

By Armonee Wilkins

Programs & Events Coordinator Armonee Wilkins analyzes the relationship between British forces and Indigenous tribes at Fort Detroit during the American Revolution.

Fort Detroit, originally established as Fort Pontchartrain du Détroit in 1701, occupies a central place in the history of colonial North America[1]. Located on a narrow waterway connecting Lake Erie and Lake Huron[2], the fort was a key hub for trade, diplomacy, and military operations. However, from its earliest days, it was a site of conflict, negotiation, and alliance between European powers and Native nations. By the time British officer Henry Hamilton arrived in the late 1770s, Detroit had already been shaped by decades of warfare and political maneuvering, a legacy that directly influenced his administration and the entries he made in the British garrison book, which is currently displayed in the special exhibition, Path to Liberty: Orders, Discipline, and Daily Life at Fraunces Tavern Museum.

The French built the fort to control trade and encourage alliances with surrounding Native nations, including the Ottawa, Huron (Wyandot), Potawatomi, and Ojibwe [3]. Yet the arrival of new tribes, such as the Meskwaki (Fox) and their allies, the Kickapoo and Mascouten, sparked violent conflict [4]. In 1712, these groups attacked the fort, taking advantage of the small French garrison. The assault nearly succeeded, but French-allied Native warriors intervened, killing or capturing hundreds of attackers and securing the fort for the French [5][6].

Control of the fort depended less on walls or soldiers and more on the alliances and support of Native nations. Native diplomacy, warfare, and knowledge of the land were decisive, shaping the trajectory of the fort long before the British ever arrived.

British Takeover and Pontiac’s Rebellion

Odawa Chief Pontiac meets with Major-General Henry Gladwin, the British commander at Fort Detroit during the siege. cOURTesY OF The Ohio History Connection

The British assumed control of Detroit in 1760, following France’s defeat in the French and Indian War [7]. While the British inherited a strategically valuable fort, they faced immediate challenges. They lacked the deep, trust-based relationships that the French had maintained with local Native nations through trade, gift giving, and diplomacy. Letters from trader James Sterling at Detroit record that he “delivered the goods to the chiefs and ensured that the presents are accepted in good order, for without their favor, trade and peace cannot be maintained at Detroit” [8]. Despite some attempts by the British to forge positive relations, their stricter trade policies, reduced gifts, and authoritarian approach to Native diplomacy created tension and resentment [9].

The 1763 Siege of the Fort at Detroit by Frederic Remington

This tension erupted in 1763 during Pontiac’s War, one of the most significant Indigenous uprisings of the colonial period [10]. Ottawa leader Pontiac organized a coalition of Native nations to challenge British authority, including a prolonged siege of Fort Detroit. Pontiac attempted a surprise attack on May 1, entering the fort with only a small party under the guise of negotiation. A few days later, he returned with hundreds of warriors hidden under blankets, hoping to seize the fort. Alerted by British intelligence, the defenders repelled the attack, forcing Pontiac to lay siege instead [11].

For months, Native warriors harassed the fort, ambushed supply parties, and carried out raids across the surrounding territory. The siege included the infamous Battle of Bloody Run, where a British raid ended in disaster, with dozens of soldiers killed or wounded [12]. By October 1763, Pontiac lifted the siege, recognizing that the fort could not be taken without French support, which never came [13]. The episode highlighted the power and strategic coordination of Native nations, demonstrating that European control was far from absolute.

Henry Hamilton and the British Garrison Book

Henry Hamilton, appointed Lieutenant Governor and commandant of Detroit, inherited a fort with a long history of Native diplomacy and frontier conflict as seen in the 1712 war. His entries in the British garrison book reveal how central Native alliances were to British strategy. Hamilton recognized that maintaining control of the region required cooperation with dozens of Indigenous nations, including Ottawa, Huron, Potawatomi, and Shawnee, among others.

Hamilton relied on Native allies for intelligence, raiding operations, and protecting British interests along the Ohio River and into Kentucky. For example, in December 1775, he issued a bounty for John Dodge, who had been “presumed to traffic with the Savages without a permit” and whose actions were suspected of supporting the Patriots [14]. Hamilton’s records show a careful awareness of how individuals could influence Native alliances and the broader balance of power in the region.

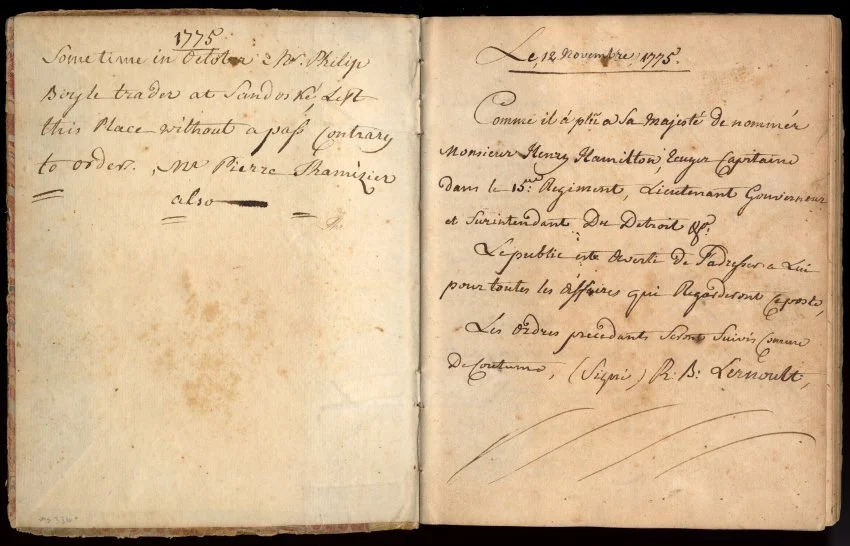

bRITSH gARRISON bOOK, MS336, Courtesy of Fraunces Tavern Museum

By January 1776, Dodge had joined the Patriots in Virginia, guiding them through “Indian Countries.” Hamilton responded by cautioning traders at British posts to avoid “giving cause of distrust or complaint to any of his majesty’s faithful Indian allies.” [15] These entries underscore Hamilton’s understanding that their hold on Native loyalty was delicate and had to be nurtured through careful diplomacy, fair treatment, and consistent communication.

bRITSH gARRISON bOOK, MS336, Courtesy of Fraunces Tavern Museum

Hamilton’s garrison book also documents the distribution of gifts to Native nations — a practice critical to sustaining alliances [16]. Such gifts were not merely ceremonial; they reinforced bonds, symbolized British respect for Indigenous authority, and helped secure cooperation in military campaigns. Hamilton knew that without the support of Native warriors, the fort could not defend itself, and British influence in the western frontier would collapse.

During the American Revolution, Hamilton used these alliances strategically. Native warriors, working with him, conducted raids that slowed American settlement and military advances in Kentucky and the Ohio Valley [17]. Settlers later referred to 1777 as the “year of the bloody sevens,” [18] reflecting the intensity and impact of these campaigns. Hamilton managed these alliances carefully, using both military planning and good relationships with Native nations to keep British control on the frontier.

Conclusion

Henry Hamilton surrenders Fort Sackville to George Rogers Clark. Illustration by Frederick Coffay Yohn.

The news of the peace treaty that ended the war, reached Fort Detroit on May 6, 1783; however, Britian held onto the fort until 1796 [19], 13 years after the Treaty of Paris was signed. The British garrison book from Fort Detroit offers a rare and invaluable window into life on the frontier during the Revolutionary era. Written in Henry Hamilton’s own hand, it documents more than just military orders and troop movements. The entries reveal how the British managed complex relationships with Native nations, coordinated raids and defenses, distributed gifts, and maintained authority in a contested region.

While Fort Detroit itself was shaped by decades of conflict, diplomacy, and shifting alliances, the garrison book provides a concrete, day-to-day record of how these choices and events played out. Each page captures the careful balance of strategy, diplomacy, and negotiation that defined the fort, making the book an indispensable source for understanding the intertwined histories of the British military and Indigenous peoples on the frontier. Visitors can view the British Garrison orderly book on display at the Fraunces Tavern Museum in our Path to Liberty: Orders, Discipline and Daily Life exhibition.

Footnotes

[1]“Fort Pontchartrain du Détroit,” Wikipedia, last modified October 30, 2025,

[2]“Fort Pontchartrain du Détroit.”

[3]Gregory Evans Dowd, Spirited Resistance: The North American Indian Struggle for Unity, 1745–1815 35–40.

[4]“Fort Pontchartrain du Détroit.”

[5]Gregory Evans Dowd, Spirited Resistance, 25–30

[6]“Fort Pontchartrain du Détroit,” Wikipedia

[7] “Fort Pontchartrain du Détroit,” Wikipedia,

[8] “James Sterling Letter Book, July 8, 1761–October 1765”

[9] Robert M. Cassidy, The British Capture of Detroit: Strategy and Frontier Diplomacy, 21–24.

[10] Dowd, Spirited Resistance, 58–63.

[11]U.S. Army Center of Military History, The Siege of Detroit

[12] U.S. Army Center of Military History, The Siege of Detroit

[13] Dowd, Spirited Resistance, 62–63.

[14] British Garrison Book, Fort Detroit, entries December 9, 1775; January 5, 1776; 1777, as digitized in Library of Congress collections

[15] Hamilton, Henry. British Garrison Orderly Book, Fort Detroit, 1775–1788

[16]British Garrison Book, Fort Detroit

[17]“Fort Pontchartrain du Détroit.”

[18]British Garrison Book, Fort Detroit

[19]“Fort Pontchartrain du Détroit.”

References

Cassidy, Robert M. The British Capture of Detroit: Strategy and Frontier Diplomacy. Kent State University Press, 2010.

Dowd, Gregory Evans. Spirited Resistance: The North American Indian Struggle for Unity, 1745–1815. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992.

“Fort Pontchartrain du Détroit.” Wikipedia. Last modified October 30, 2025. Fort Pontchartrain du Détroit - Wikipedia

Hamilton, Henry. British Garrison Book, Fort Detroit, entries December 9, 1775; January 5, 1776; 1777. Digitized by Library of Congress. https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/rbc/rbpe/rbpe22/rbpe223/2230070a/2230070a.pdf.

“Henry Hamilton.” Battlefields.org. Accessed December 9, 2025. https://www.battlefields.org/learn/biographies/henry-hamilton.

U.S. Army Center of Military History. The Siege of Detroit (CMH Publication 74-1). https://history.army.mil/Portals/143/Images/Publications/Publication%20By%20Title%20Images/D%20PDF/CMH_Pub_74-1.pdf.

James Sterling Letter Book, July 8, 1761 – October 1765. James Sterling Letter Book (1761‑1765), William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan Digital Collections. https://quod.lib.umich.edu/s/sterlingj/sterlingj.0001.001 (accessed December 9, 2025).

AllThingsLiberty. “War and Conflict in the Ohio Country During the American Revolution.” October 2023. War and Conflict in the Ohio Country during the American Revolution - Journal of the American Revolution

AllThingsLiberty. “The Treaty of Fort Pitt (1778): The First U.S.–American Indian Treaty.” December 2018.The Treaty of Fort Pitt, 1778: The First U.S.–American Indian Treaty - Journal of the American Revolution

AllThingsLiberty. “Under the Banner of War: Frontier Militia and Uncontrolled Violence.” March 2022. Under the Banner of War: Frontier Militia and Uncontrolled Violence - Journal of the American Revolution

Library of Congress. British Garrison Orders, 1775–1788. https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/rbc/rbpe/rbpe22/rbpe223/2230070a/2230070a.pdf.