Noah Duell, Senior Development Officer | February 2026

A closer look at three letters in the archives of Fraunces Tavern Museum reveals the pathbreaking preservation philosophy of William H. Mersereau, the architect responsible for the restoration of Fraunces Tavern beginning in 1907.

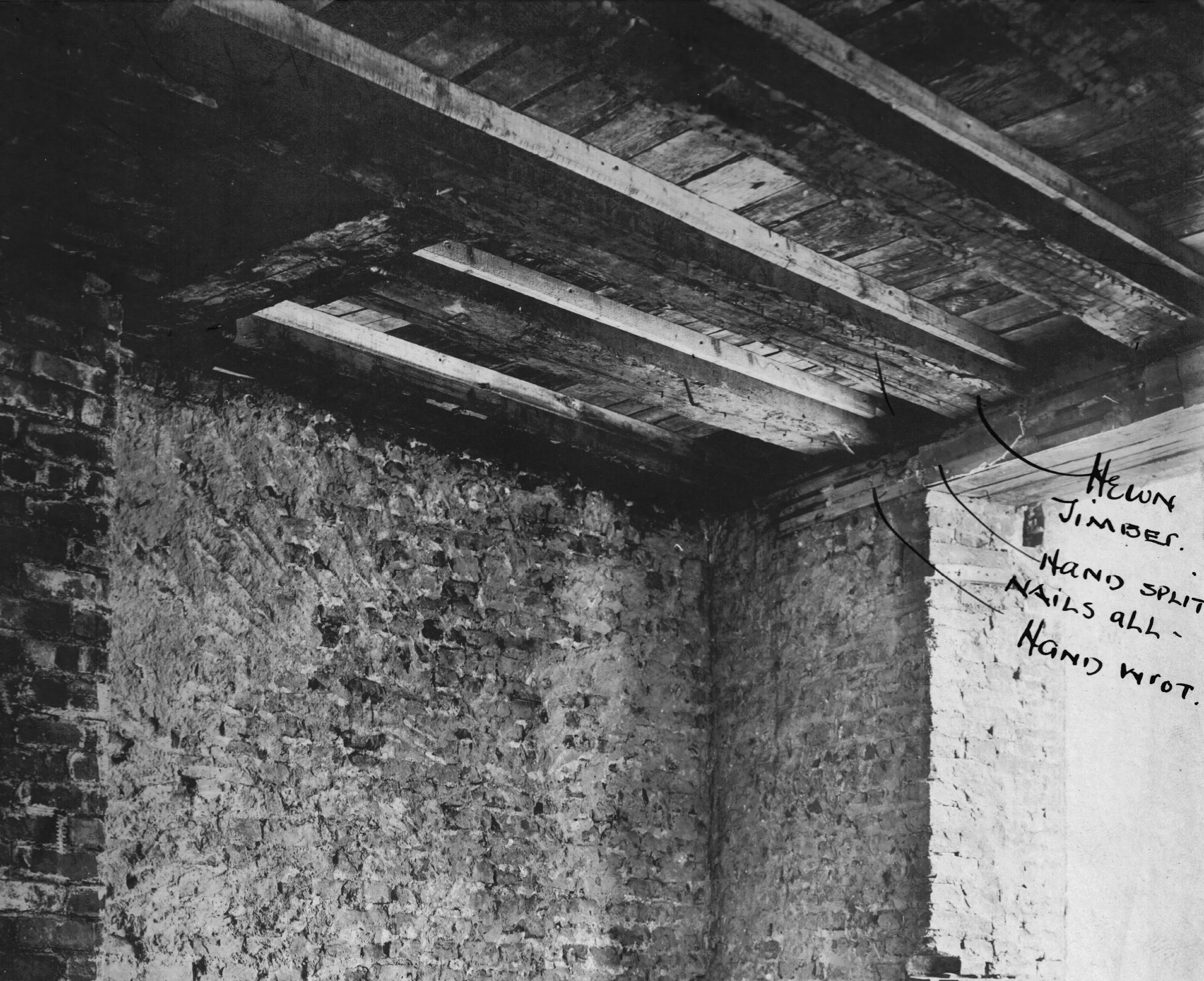

The southwest corner of the Long Room, taken during the restoration, ca. 1906. Annotations on the image note hand wrought nails and hewn timbers, all original to the space. Fraunces Tavern Museum collection.

In the extensive collection of Fraunces Tavern Museum are three letters among others from architect William H. Mersereau to Morris P. Ferris, the Secretary of Sons of the Revolution. Exchanged in early 1905, these letters offer particularly valuable insight, not just into the condition of Fraunces Tavern before its restoration, but into the philosophy and character of its architect. More than two decades before Rev. W. A. R. Goodwin and John D. Rockefeller, Jr. inaugurated their project at Colonial Williamsburg, Mersereau laid out a visionary path to restore Fraunces Tavern in New York City to “the way [it] looked when Washington visited it.” [1]

The Fraunces Tavern that Mersereau encountered in 1905 was quite different from that which Washington knew. In the 19th century, owners after Samuel Fraunces rearranged and built upon the Tavern, obscuring much of its 18th century core and appearance. Mersereau reported as much in his first letter, dated January 23, 1905. “As requested,” he wrote, “I have measured up the building and now present the same on paper as near as it is possible under existing conditions to plot same, it being very difficult to measure up a building occupied, as this one is, and with no chance to break away ceilings or plaster to determine any material, etc.” [2]

A vision of the Tavern’s 18th century appearance nevertheless emerged from Mersereau’s analysis. Much of the brick on the Broad Street façade, he wrote, was “very probably Dutch,” and there was valuable “Philadelphia front brick” on the Pearl Street façade. “It is evident to my mind that the building was originally of three stories from the evidence given by [the] brickwork,” he concluded, as “the second and third story fronts are clearly the original brick…” [3]

In the interior, Mersereau uncovered an extensive amount of original fabric, especially in the Long Room. By unearthing the chimneys, Mersereau reasoned, he could determine the original orientation of the room. “I believe that when opened,” he wrote, “the old soot will be found on the brick linings of the fireplace.” [4] Here, too, his supposition was correct, and it provided a firm basis for the restoration.

He concluded his January letter with some ideas for the use of the Long Room following its restoration. “The Long Room would naturally be the museum,” he wrote initially, but a hand in pencil, probably his own, interlined another idea: “The Long Room would naturally be retained as nearly as possible as of the time of Washington.” [5] This purpose it continues to serve today.

Sometime between January 23 and March 13, 1905, Mersereau was able to undertake a deeper and more thorough investigation, one which led to his final conclusions related to the restoration. “[T]he present barren interior,” he suggested “was not always so… The Van Cortlandt, and [Philipse] families”—of which the Tavern’s original builders, Stephen Delancey and Anne (Van Cortlandt) Delancey were a part—“have left indubitable evidence in their country houses that they were abreast of the best work of the time abroad.” By this, he meant Van Cortlandt Manor in Croton-on-Hudson and Philipse Manor in Yonkers. “In the finish of [the] interior then it would seem eminently proper that we follow these models, as it is hardly likely they made their town house any less finished than their country seats.” [6] Mersereau’s choice of precedent was thus deliberate and sensitive in the instances where no original fabric was in place.

Three days after writing his March letter, Mersereau sent another to confirm his own bona fides. “In considering my definite appointment as architect for the proposed restoration of Fraunces Tavern,” he wrote, “I would ask that the fact that I have been identified with considerable restoration work on buildings that date back as far as 1697 and even further be taken into consideration.” Mersereau stated that his “association with buildings of this time has naturally led to a close study of old work and environment and it is work that I like better than any other.” Among these was his work at Washington Irving’s Sunnyside in Tarrytown, New York, where he designed a historically sympathetic addition for the then-owner; at the Old Dutch Church in Sleepy Hollow, New York, where he made the structure “nearly as possible what it was in 1698”; at the Old Swede’s Church in Wilmington, Delaware, where he uncovered the original brick floor; at Westover, William Byrd’s mid-18th century James River plantation in Tidewater Virginia, where he designed a new wing that made the house symmetrical; and with a proposed restoration of Bruton Parish Church in Williamsburg, Virginia, which was never carried out. [7]

Few other architects could match Mersereau’s resume at this point, yet his restoration work was not without its critics. [8] The New York Times, for example, published an article on March 17, 1907, titled “The ‘Restoration’ of Fraunces Tavern; Sons of the Revolution Will Reopen Famous House Now Radically Changed—Architect Replies to Sharp Criticism of the Transformation.” The editors wrote that “[c]ritics are not lacking who, from a study of the tavern as it stands to-day, declare that in a number of essential particulars it does not appear as it was in Washington's time.” [9]

In his response, Mersereau was direct and unflinching. Of what the editors called the “chief fault” of the restoration—that is, the roof line—Mersereau wrote that it was “…made on the exact slope of [the] old line. Since the plaster has been further stripped the old line has been clearly proved correct, the bricks above the line being entirely different in measurement from the bricks below the line.” As for the Long Room, “[t]he selfsame beams on which Washington stood are there beneath the floor of the ‘Long Room’ to-day, and the tier above is the same and the old walls are the same.” The room “contained not a vestige of woodwork, sash, &c., that it had in Washington’s time,” but “…[t]he old hewn beams, however, exist still in the hallway, in the floor and ceiling of the ‘Long Room,’ and in the floor and ceiling of the second and third stories on Pearl Street.”

Mersereau concluded that “…[i]f those who hold to the opinion that ‘nothing of the old tavern is left after this restoration’ would really investigate matters, they could very easily prove to their entire satisfaction that not a piece of the old brickwork, not a stick of the old timber has been removed that could be possibly left in its original position.” [10] A detailed survey by leading architectural historians starting in 2021 confirmed as much.

With diligence and sensitivity, William H . Mersereau completed the restoration of Fraunces Tavern, and Sons of the Revolution in the State of New York, Inc. opened it as a museum and restaurant on December 4, 1907. Mersereau stated in The New York Times that “Fraunces’s Tavern will be, when completed, more nearly as Washington saw it than it has been at any time during the last century,” and indeed it continues to be.

Notes

1. William H. Mersereau to Morris P. Ferris, March 13, 1905, 1. See here for a PDF of that letter.

2. William H. Mersereau to Morris P. Ferris, January 23, 1905, 1. See here for a PDF of that letter.

3. William H. Mersereau to Morris P. Ferris, January 23, 1905, 2.

4. William H. Mersereau to Morris P. Ferris, January 23, 1905, 5.

5. William H. Mersereau to Morris P. Ferris, January 23, 1905, 6.

6. William H. Mersereau to Morris P. Ferris, March 13, 1905, 1–2.

7. William H. Mersereau to Morris P. Ferris, March 16, 1905, 1–2. See here for a PDF of that letter.

8. It may be helpful to place Mersereau’s approach alongside other contemporary restoration projects in the United States. In 1902, America’s leading architecture firm, McKim, Mead & White, undertook a restoration of the White House at the behest of President Theodore Roosevelt. Their task, like that of the Mersereau after them, was to remove the 19th century “excrescences” and restore the space to its early appearance. Similarly, a group of Philadelphia architects completed the restoration of Independence Hall in 1913, removing “the accretions of a century” and returning it to its original appearance. For accounts of these restorations, see, respectively, McKim, Mead & White, Restoration of the White House: Message of the President of the United States Transmitting the Report of the Architects (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1903). Retrieved from https://www.google.com/books/edition/Restoration_of_the_White_House/v1YAAAAAYAAJ?hl=en; and “Restoration of Congress Hall, Philadelphia, Pa.,” in Journal of the American Institute of Architects, vol. 1, no. 12, December 1913, 546–549. Retrieved from https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=msu.31293027928658&seq=1 (page 273 in document).

9. “The ‘Restoration’ of Fraunces’ Tavern; Sons of the Revolution Will Reopen Famous House Now Radically Changed-Architect Replies to Sharp Criticism of the Transformation,” The New York Times, March 17, 1907, Section M, Page 11. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/1907/03/17/archives/the-restoration-of-fraunces-tavern-sons-of-therevolution-will.html; The New York Times archive has this article split in two—for the second section containing Mersereau’s response, see note ten.

10. ““How Fraunces’s Tavern Was Restored by William H. Mersereau,” The New York Times, March 17, 1907, Section M, Page 11. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/1907/03/17/archives/how-frauncess-tavern-was-restored-turned-into-atavern-restoration.html.